Sassafras albidum

Sponsor

Kindly sponsored by

Peter Hoffmann

Credits

Article from Bean's Trees and Shrubs Hardy in the British Isles

Recommended citation

'Sassafras albidum' from the website Trees and Shrubs Online (treesandshrubsonline.

Genus

Common Names

- Sassafras

Synonyms

- Laurus albida Nutt.

- S. officinale var. albidum (Nutt.) Blake

- S. variifolium var. albidum (Nutt.) Fernald

- Tetrantha albida (Nutt.) Spreng

- Sassafras albidum var. molle (Raf.) Fernald

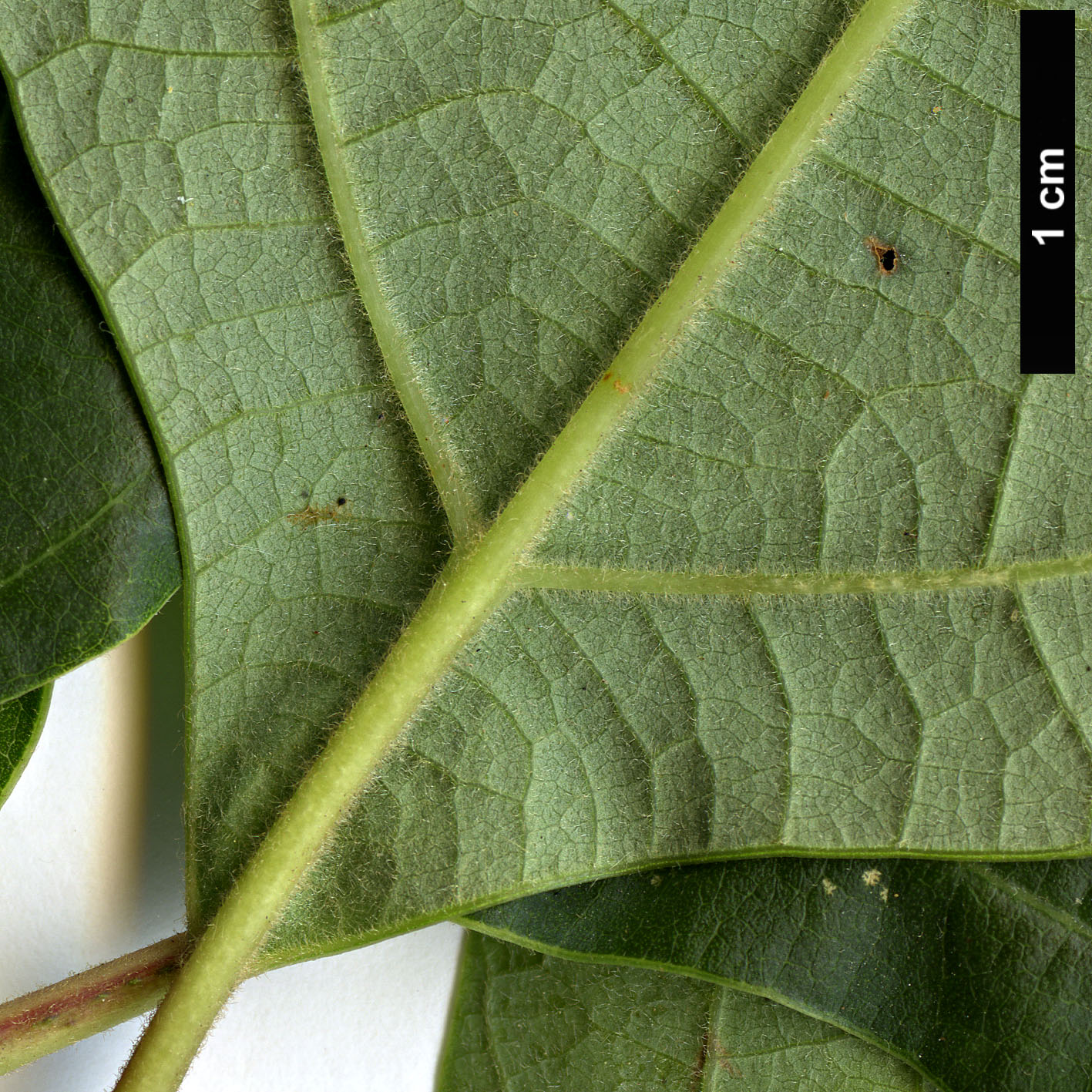

Medium to large deciduous trees 9 m – 20 m (occasionally 30 m) tall. Bark is red-brown and deeply furrowed with age. Young stems green with dark mottling, somewhate terete and aromatic when crushed. Leaf blade is pinnately veined, papery, ovate, 8 cm – 18 cm × 5 cm – 12 cm, apex acute to obtuse, base cuneate. Leaves are alternate and may be unlobed, 2 – lobed with an obvious main lobe and smaller one like a mitten, or 3 – lobed with an entire margin all appearing on the same branch. Both young stems and leaves may be glabrous to downy across the plant’s wide natural range with some taxonomists designating plants with more persistent down as var. molle. Plants are dioecious. Inflorescence to 4 cm, flowers small, greenish-yellow, with lemony fragrance in spring. Fruit a drupe, blue–black, 1 cm carried on a reddish cupule in late summer.

Plants often forming dense colonies especially in disturbed areas.

Distribution Canada Ontario United States Maine to Florida west to Iowa, Kansas, and Texas

Habitat Forests and woodlands, disturbed sites such as old fields, fencerows, and roadsides.

USDA Hardiness Zone 4-9

A medium to large tree with distinctive foliage appearing as simple unlobed leaves, mitten-like with 2 lobes, one lobe always central and larger than the other in both right and left hand versions, or symmetrical with 3 lobes. Leaves take on bright gold and orange color in the fall. Growth rate is quite fast, as much as 65 cm per year. Plants can form aggressive thickets from root sprouts in some locations. The wood has a spicy smell and taste and was once used in the manufacture of root beer and some commercial dental products. Some indigenous peoples used sassafras twigs as chewing sticks.

Where growing naturally, sassafras is easy and long-lived. It prefers moist, rich, well-drained acidic soils and will often become chlorotic in alkaline spots. Field grown plants can be difficult to transplant and should only be dug and moved in early spring. Root suckers will often need to be removed regularly from these plants. Sassafras is easier and more forgiving if container grown and will transplant easier at other times of the year. In all cases newly installed plants should be kept watered until well established.