Ostrya virginiana

Sponsor

Kindly sponsored by

Claire Mansel Lewis

Credits

Owen Johnson (2022)

Recommended citation

Johnson, O. (2022), 'Ostrya virginiana' from the website Trees and Shrubs Online (treesandshrubsonline.

Genus

Common Names

- Ironwood

- Deerwood

- Leverwood

- Hardhack

- Indian Cedar

- Bois de Fer

Synonyms

- Carpinus virginiana Mill.

- Carpinus ostrya L., in part

- Ostrya virginica Willd.

- Ostrya virginiana var. glandulosa (Spach) Sarg.

- Ostrya virginiana var. lasia Fernald

- Ostrya virginiana subsp. lasia (Fernald) E. Murray

Infraspecifics

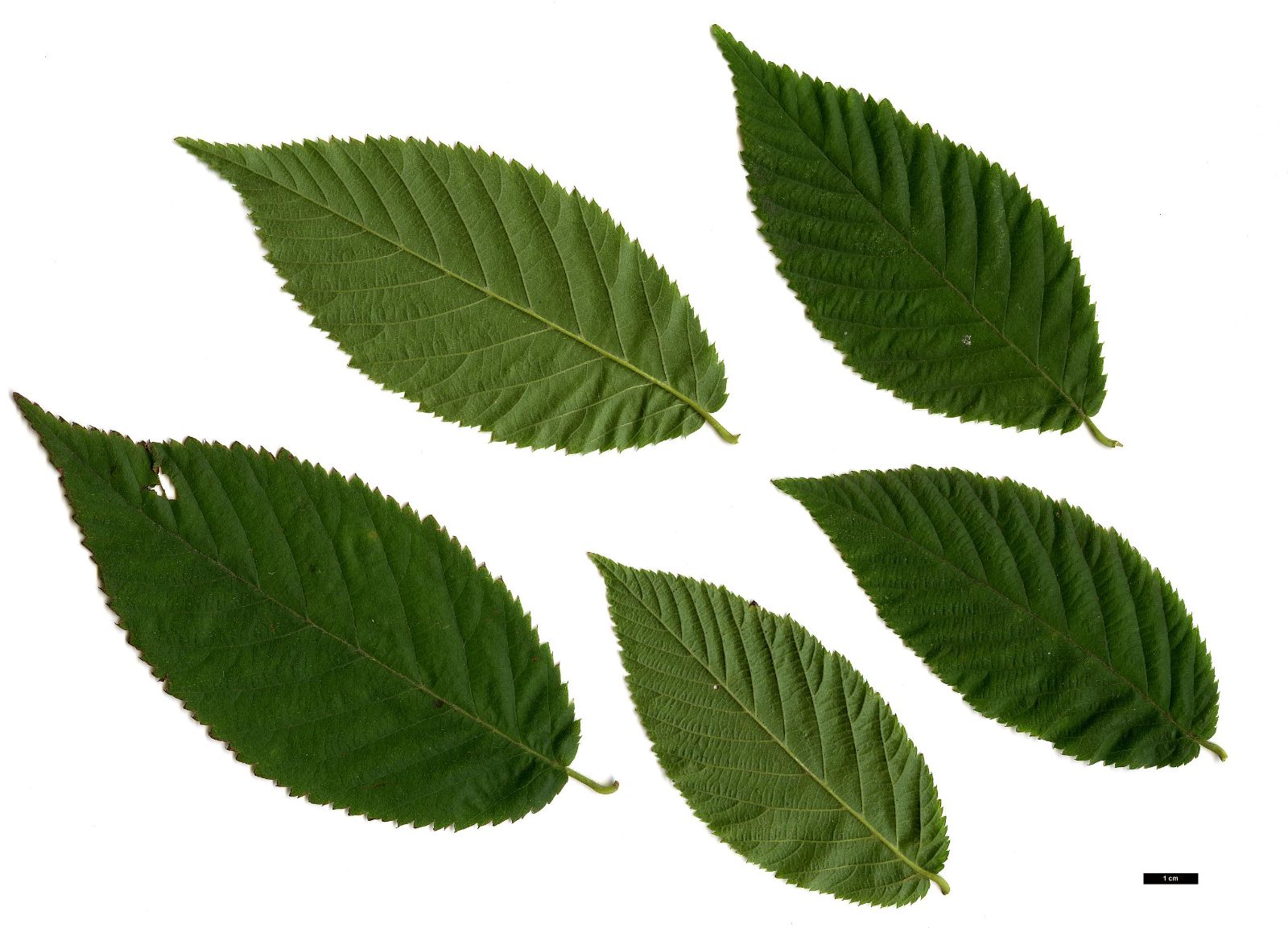

Tree to c. 18 m, with a spreading habit and an often short bole. Bark grey to brown, soon with narrrow, very scaly ridges. Twigs red-brown, often zig-zag, often with dense typically gland-tipped hairs; buds 3–6 mm long, narrowly ovate and spreading from the twig. Leaves 5–10 × 2–5 cm, oval-lanceolate; sharply and sometimes doubly-toothed; hairy on the midrib and between the veins above and more generally so beneath; lateral veins in 12–15 pairs; petiole c. 6 mm long, with sometimes glandular hairs. Male catkins 2–5 cm long; fruiting catkins 3–7 cm, bladders 10–18 mm long, hairy at the base; nutlet large (c. 6 mm long). (Bean 1976; Furlow 1997; Dirr 2009).

Distribution Canada Manitoba, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Québec United States Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming

Habitat Free-draining forest slopes and rocky ridges, less often on flood-plains.

USDA Hardiness Zone 2

RHS Hardiness Rating H7

Conservation status Least concern (LC)

The common hop-hornbeam of eastern North America is one of the toughest of trees, growing as an understorey species in often dry and gravelly soils; Carpinus caroliniana, with very similar leaves but a smooth bark, tends to take over in the moister soils of river valleys. Ostrya virginiana (subsp. virginiana) is long-lived in the wild, reaching at least 300 years (Stewart 2010). It is one of the trees that was introduced to England in the late 17th century for Henry Compton, a Bishop of London (and Virginia) who had a keen interest in botany; Compton was growing it at Fulham Palace in London in 1692 (Bean 1976), meaning that it was established in cultivation by the time that its European ally, Ostrya carpinifolia, reached Britain in the 1720s. The two species are remarkably similar – so much so that labels, even in well curated collections, sometimes have to be questioned – and O. virginiana is even more likely to be confused with the east Asian O. japonica, which shares its sometimes microscopically gland-tipped hairs.

On the evidence of several flourishing trees at Kew which are currently grown as Ostrya virginiana and were up to 15 m tall in 2022 , this is a more reliable plant in cool temperate regions than Carpinus caroliniana; there is one thriving representative (13 m × 46 cm dbh in 2014) as far north as the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (Tree Register 2022). Like the hornbeam, and like O. carpinifolia, its autumn colour is yellow, but this can start particularly early – even in August (Rushforth 1986).

Even in America this tree is little used as an ornamental, despite its extraordinary hardiness and drought tolerance and the ornamental qualities which are shared across the genus; it has a reputation of being slow to establish (Dirr 2009). In the UK, Ostrya virginiana has certainly lost out in popularity to its European look-alike, and in 2020 was advertised by only one Plant Finder nursery (Royal Horticultural Society 2020). The London Street Tree database (https://apps.london.gov.uk/street-trees/) includes a couple of records, but the difficulties in distinguishing this tree from its commoner European ally should be borne in mind here. One avenue of large standards was planted at the Belfast Botanic Gardens in 2007 (Friends of Belfast Botanic Gardens 2022).

As is the case with Carpinus caroliniana, populations of Ostrya virginiana from the Atlantic Coastal Plain are distinct and are sometimes given varietal or subspecific status (O. virginiana var. lasia Fernald or subsp. lasia (Fernald) E. Murray), though this is treated by Plants of the World Online (202) as synonymous with subsp. virginiana: the leaves are smaller, blunter and often downier (Furlow 1997), but this population has been little-studied and authorities are less likely to recognise it as taxonomically distinct than the equivalent variant of C. caroliniana (subsp. caroliniana). Compton’s original introduction presumably derived from this coastal population, but the origins of today’s trees in Europe are seldom recorded. The younger of two O. virginiana in Sir Harold Hillier Gardens was collected in eastern Canada (Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh 2022).

'Camdale'

Synonyms / alternative names

Ostrya virginiana SUN BEAM™

RHS Hardiness Rating: H7

USDA Hardiness Zone: 3

A clone selected from the local population by North Dakota State University for its hardiness (to USDA hardiness zone 3) and for is neat habit, spire-like at first; it was distributed in 2011 (Hatch 2021–2022). Even in older plants, about half the dead leaves hang on through winter.

'Frizam'

Synonyms / alternative names

Ostrya virginiana FRIENDSHIP™

Selected by Lake County Nursery in Ohio and sold by 2014; a low spreading tree with good autumn colour (Hatch 2021–2022).

'JFS-KW5'

Synonyms / alternative names

Ostrya virginiana AUTUMN TREASURE™

A narrow, rather upright selection with good autumn colour, sold by J. Frank Schmidt and Son of Oregon from 2015 (Hatch 2021–2022), and gaining popularity by 2022 in Canada and the United States.

subsp. guatemalensis (H.J.P. Winkl.) A.E. Murray

Common Names

Mexican Hop-hornbeam

Synonyms

Ostrya guatemalensis (H.J.P. Winkl.) Rose

Ostrya italica var. guatemalensis H.J.P. Winkl.

Ostrya mexicana Rose

Ostrya virginiana var. guatemalensis (H.J.P. Winkl.) J.F. Macbr.

Trees from Mexico and central America, resembling Ostrya virginiana in leaf size, venation and the usual presence of glandular hairs, but probably genetically diverse.

Distribution

- El Salvador

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Mexico

RHS Hardiness Rating: H5

USDA Hardiness Zone: 6

Very much as is the case within the genus Carpinus, the populations of Ostrya in Mexico and central America has been little-studied, and botanists from the United States tend to treat all of them as synonymous with the common North American O. virginiana. But there is a gap in distribution – again very similar to that of Carpinus – between the southern limits of the range of the United States’ O. virginiana in northern Texas, and the Mexican trees found, for example, in the mountains of Nuevo León, implying that these two populations have at the very least radiated from separate Ice Age refugia. Only one Carpinus species is known from the United States, but in Ostrya the situation is further confused by the presence of O. chisosensis very near the Mexican border in southern Texas and of O. knowltonii a little further west: O. chisosensis has also been reported from northern Coahuila in Mexico (Poole, Carr & Price 2007), while trees similar to O. knowltonii have been observed in north-western Mexico (Furlow 1997). Ostrya populations from the subtropical cloud forests of El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and southern Mexico look much more like O. virginiana, and purely for convenience this account follows Plants of the World Online (Plants of the World Online 2022) in treating these as a subspecies. Ostrya of similar appearance were also reported from species-rich temperate forests much further north in 1990, from the valley of La Trinidad south of Monterrey, Nuevo León, by Rob Nicholson et al., during an expedition to collect Taxus globosa for the Arnold Arboretum (R. Nicholson pers. comm). It is a reasonable assumption that these various Mexican populations are quite genetically diverse; the assessment of subsp. guatemalensis as Near Threatened relates specifically to cloud-forest trees from central America (Shaw et al. 2014).

In cultivation, Ostrya of this sort are represented by a tree at the University of California Botanical Garden at Berkeley, grown from seed collected by Dennis Breedlove in 1976 in central Chiapas in the far south of Mexico (University of California Botanical Garden 2022); this population might not be hardy much further north. The seed collected by Rob Nicholson in Nuevo León in 1990 (Nicholson D3) was distributed quite widely (R. Nicholson pers. comm.), and examples have been traced at Keith Rushforth’s arboretum in Devon, UK, 5 m tall in 2013 (Tree Register 2022), and at Arboretum Wespelaar in Belgium, where three beautifully straight-stemmed and shapely young trees seem untroubled by winter cold (R. Nicholson pers. comm.).