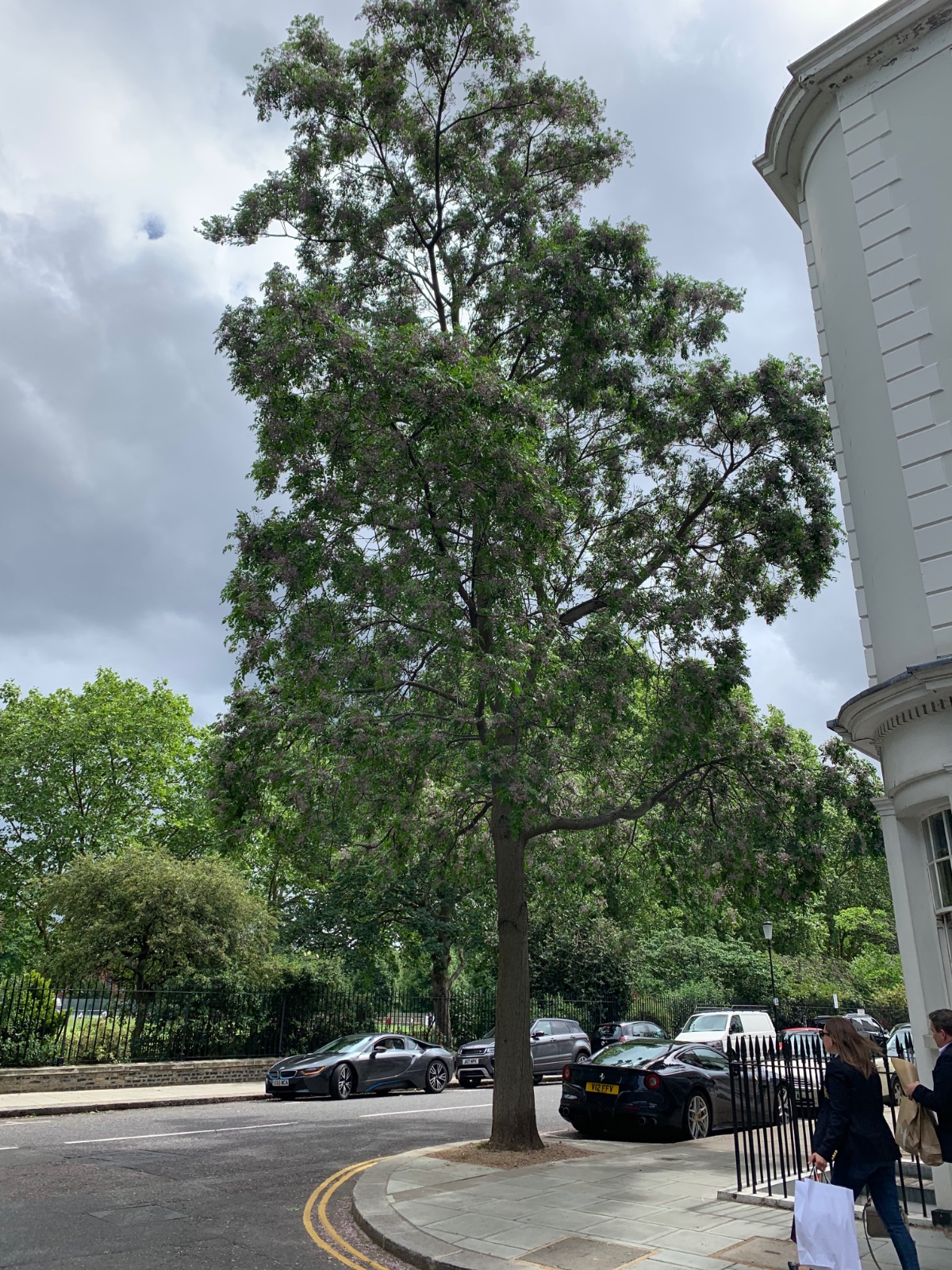

Melia azedarach

Credits

Article from Bean's Trees and Shrubs Hardy in the British Isles

Recommended citation

'Melia azedarach' from the website Trees and Shrubs Online (treesandshrubsonline.

Genus

Common Names

- Bead Tree

A deciduous tree up to 30 or 40 ft high in warm countries; variable in habit. Leaves alternate, doubly pinnate, 12 to 24 in. long, half as much wide; leaflets ovate to oval, slender-pointed, unequally tapered at the base, toothed or lobed, 11⁄2 to 2 in. long, 1⁄3 to 3⁄4 in. wide, quite glabrous, or sometimes slightly downy on the midrib and main-stalks when young. Flowers fragrant, 3⁄4 in. wide, numerous in clusters of loose axillary panicles 4 to 8 in. long on the young leafy shoots. Calyx five-lobed, the lobes oblong, pointed, downy, 1⁄8 in. long. Petals five, lilac-coloured, narrow-oblong, 1⁄8 in. wide, spreading or slightly reflexed. Stamens ten or twelve, their stalks united into a slender, erect, violet-coloured tube about 1⁄4 in. long, the anthers only free. Fruits yellow, roundish egg-shaped, 1⁄2 in. long, containing a hard, bony seed.

Native of N. India and of C. and W. China; now cultivated or naturalised in almost every warm temperate or subtropical country, often as a street tree. According to Gerard, it was cultivated by John Parkinson in England at the end of the 16th century. Miller says he flowered it at Chelsea three or four years successively, and that he found it stood cold extremely well in the open ground. I have never heard of its being grown near London in recent years except under glass. So far as I know, Hiatt C. Baker of Oaklands, near Bristol, succeeded as well as anyone with it. He grew it out-of-doors against a wall, where it stood uninjured for over twenty years. He showed a spray gathered from this plant at Westminster in June 1930. I have seen it in flower in S. Italy, in Dalmatia, and on the Riviera, and have always been charmed by the grace and beauty of its foliage and blossom. It is easily raised from imported seed, is of easy cultivation, and flowers at an early age. The name of ‘bead-tree’ originated through the seeds being strung by monks and others to form rosaries.

var. umbraculiformis Berckmans is much grown in the S.W. United States as the ‘Texan Umbrella Tree’. It forms a dense, flattened, spreading head of branches, and has narrower leaflets. Said to have appeared originally on the battlefield of San Jacinto, Texas.

'Jade Snowflake'

This remarkable, very heavily variegated cultivar was found in a farmyard in San Antonio, Texas, in 1989, but it is reported to be unstable, reverting to green on occasion (Dirr 2009). It can form an attractive small tree 6–10 m tall, its pallor effective in light shade. It comes true from seed if grown in isolation from normal specimens (Dirr 2009).