Carrierea calycina

Sponsor

Kindly sponsored by

William & Griselda Kerr

Credits

Owen Johnson (2022)

Recommended citation

Johnson, O. (2022), 'Carrierea calycina' from the website Trees and Shrubs Online (treesandshrubsonline.

Other taxa in genus

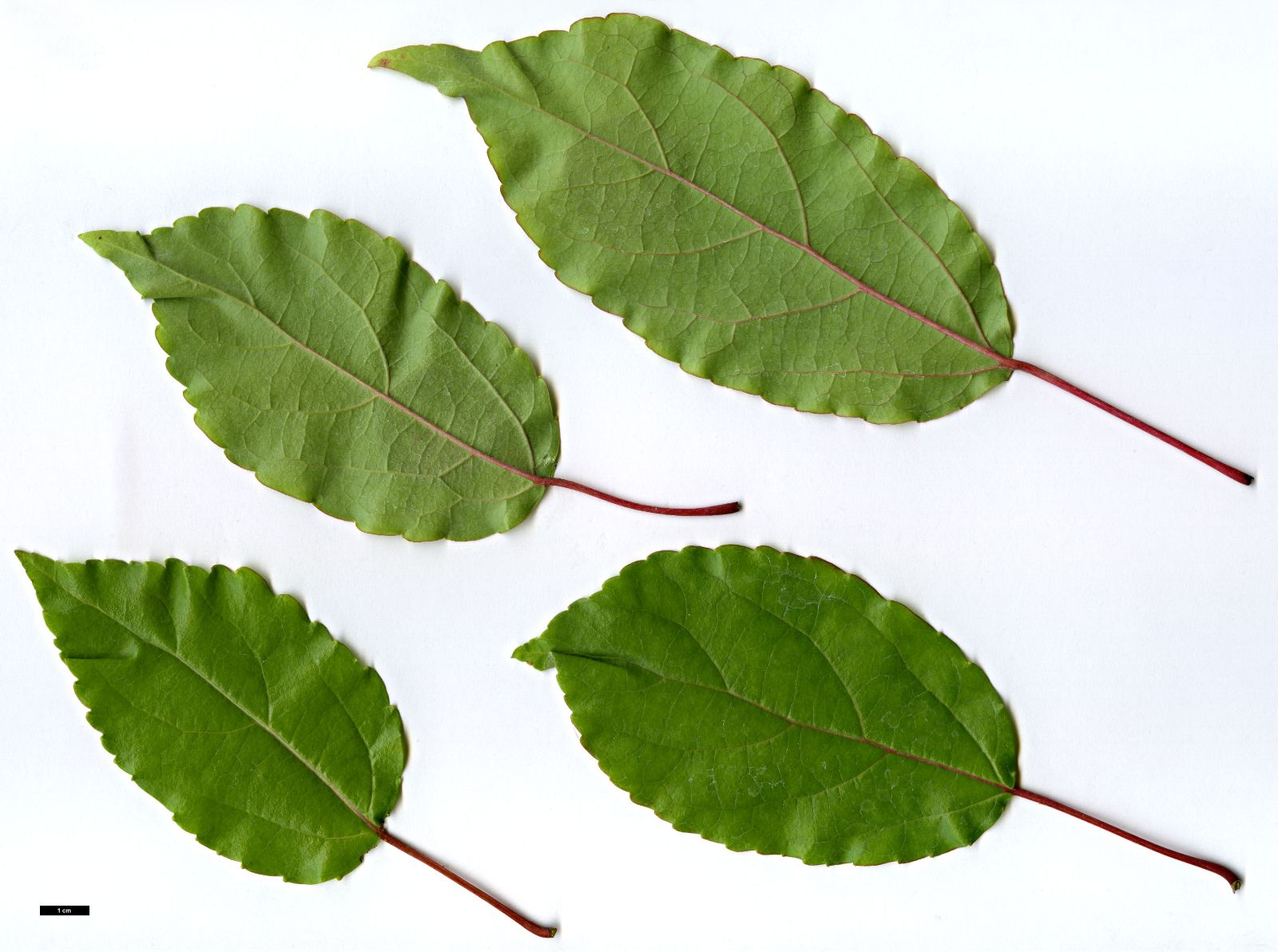

A tree to 16 m tall, with one or several straight stems from the base; foliage often arranged in tiers. Bark brownish-grey, smooth, with darker lenticels. Twigs grey, glabrous; buds reddish, blunt. Leaf thinly leathery, waxy-surfaced on both sides, deep green above and paler beneath, ovate or elliptic to oblong or slightly obovate, 9–14 × 4–6 cm; glabrous, or sparsely tomentose under the veins; base rounded to cordate, tip abruptly pointed and usually with a distinct, acuminate ‘drip-tip’; veins pale and conspicuous, in 4 or 5 pairs, with 3 veins from the base; margin with quite large, rounded, regular teeth, each tipped with a conspicuous pale gland; leaf flushing reddish; petiole 3–7 cm, often red in sun, glandular. Inflorescence terminal, candelabrum-like, to 10 cm high, heavily scented. Sepals to 2 cm long, pale green maturing greeny-white or yellowish or rarely blush-pink, cordate, forming a cup-shaped flower 30 mm long. Fruit capsule fusiform, slightly curved, 3–8 cm, woolly; seed including wing 10–15 mm long. Flowers (in wild) May-June, fruits July-October. (Flora of China 2022; Bean 1976).

Distribution China Guangxi, Guizhou, Hubei, Hunan, Sichuan, Yunnan

Habitat Forest glades and margins, 1300–1600 m asl; a pioneer species.

USDA Hardiness Zone 7

RHS Hardiness Rating H5

Conservation status Least concern (LC)

Carrierea calycina is an example of a tree introduced just once to western gardens during the first golden age of Asiatic plant exploration in the first decade of the twentieth century, and re-introduced by just one collector during the second golden age, in the last decade of that century. The first seed was collected by Ernest Wilson in Sichuan in 1908 (W 1212), and was successfully germinated at Veitch’s Nursery in England; specimens reached the flowering stage at gardens including Borde Hill and Bodnant, and the first flowers were in Captain and Mrs Desborough’s Dorset garden, ‘Tulgey Wood’, in 1929 (Bean 1976) – although the example at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, died in the 1930s without having flowered. The best known representative of this original population, at Birr Castle in central Ireland, only began to flower as a mature tree in 1999 and was 15 m tall with a trunk 44 cm thick in 2014 (Tree Register 2022); it was blown down in 2018. Another Irish example, at Rowallane in Co. Down, has languished in dense shade and is only 6 m tall (Tree Register 2022), and did not flower until 2010 when it was probably 91 years old, but is the only known survivor from this first generation of what is clearly never a very long-lived tree. An example in the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh was noted in 1959 by a visiting American botanist, Frederick Meyer, having withstood all the mid-twentieth century’s harsh winters (Meyer 1959).

Like another unrelated Chinese tree which has the same kind of aristocratic grace to its foliage, Emmenopterys, Carrierea has clearly suffered from its reputation of being shy to flower in cultivation. As a pioneer species of woodland glades (University of British Columbia Botanical Garden 2022), it seems likeliest to thrive and bloom in full sun, but with some side-shelter. The flowers are richly scented (Drinkwater 2010) and certainly beautiful, suggesting a snake’s-head fritillary’s in their individual shape and greenish pallor, but with each downy sepal curiously folded and winged, a little like the petals of Kalmia or even – before they expand fully – like a Halesia seed-head. But it is hard not to feel that, if Carrierea, like its allies the willows and poplars, was wind-pollinated and pretty blossom was never expected, the species might even have retained a constant place in cultivation, as a smallish tree which is not hard to grow and whose leaves and habit have a special elegance. These leaves flush reddish – often with an orange cast rather than the magenta which is commoner among Chinese mountain plants – and the colour tends to persist on the leaf-stalk to contrast delightfully with the dark, quite shiny green of the mature leaf-blade.

One plantsman who did appreciate this tree’s varied merits was the late Peter Wharton, Curator of the David C. Lam Asian Garden at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada; in 1994 with Chinese assistance he organised an expedition to the Dashahe Cathaya Reserve in the Dalou Mountains of northern Guizhou, whose specific aim was to re-introduce Carrierea calycina to the west (VanDusen Botanical Garden 2013). The plant’s scarcity in cultivation has led some commentators to assume that this ‘is a species edging ever closer to extinction’ (Bramham 2013), but in the wild it is in fact quick to colonise new sites and has been assessed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as a plant of Least Concern. During his two-week trip, Wharton was able to make two seed collections (PW 68 and PW 84), which were quite widely distributed around the world.

In the UK and Ireland, the young trees which are now thriving and flowering in numbers of public and private gardens are all known or can be assumed to have derived from PW 68 and PW 84; most of them were passed on by the late Harry Hay, a pig-farmer and amateur horticulturalist who successfully germinated his share of the seeds on his smallholding next to Junction 8 of the M25 in Surrey (H. Hay pers. comm.). The female seedling planted by Roy Lancaster in his private garden in Hampshire was one of the first two to flower, in 2005, and was just the largest of this bunch in 2021, when it was 11 m tall and 22 cm dbh (Tree Register 2022); the species is now represented once again in the chillier climate of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, where it is bushier, but has flowered since 2010 (Drinkwater 2010). In 2022, Carrierea calycina was commercially available from PanGlobal Plants in the UK, and from Ardcarne Garden Centre in the Republic of Ireland (Royal Horticultural Society 2021). It has also been offered by Burncoose Nursery, where Charles Williams finds it ‘easy to grow’ (Burncoose Nurseries 2022), though Nick Macer’s original plant of PW 84, from which the PanGlobal Plants stock derives, suffered from canker and has been successfully coppiced (Nick Macer pers. comm.)

In the Netherlands, the species was offered in 2022 by the Kwekerij Bulk nursery in Boskoop, but it may be less well adapted to a continental European climate. As for many east Asian trees, the problem is not one of absolute hardiness but is likely to lie in the plant’s expectation of ample rainfall throughout the growing season.

Carrierea calycina is represented by various seedlings from Peter Wharton’s collections around Vancouver itself, and first flowered here after just 12 years at the VanDusen Botanical Garden (VanDusen Botanical Garden 2013). In the neighbouring United States, by contrast, the species remains virtually unknown; it is omitted from Michael Dirr’s Manual of Woody Landscape Plants (Dirr 2009), and the hardiness rating of Zone 8b suggested by some American authorities is certainly over-pessimistic. Some of Wharton’s seed went to the University of Washington Botanic Gardens in Seattle (VanDusen Botanical Garden 2013), where at least one tree (20–95*A) survived to be photographed online in 2014, though in the 1990s surplus stock was apparently being sold in the Gardens’ Calvert Greenhouse as Bretschneidera sinensis (University of British Columbia Botanical Garden 2022). In 2016 a specimen was planted in the JC Raulston Arboretum in North Carolina (JC Raulston Arboretum 2022), where summers should be adequately wet but possibly too warm for this tree to be at its best.

In New Zealand, seed was received from Peter Wharton by the Pukeiti Trust Garden at New Plymouth (VanDusen Botanical Garden 2013); a good young tree presumably raised from this source grows at Hackfalls Arboretum, also on the North Island and in a climate much milder than the species tends to experience in the wild.