Abies homolepis

Sponsor

Kindly sponsored by

Sir Henry Angest

Credits

Tom Christian (2021)

Recommended citation

Christian, T. (2021), 'Abies homolepis' from the website Trees and Shrubs Online (treesandshrubsonline.

Genus

Common Names

- Nikko Fir

- Dake-momi

- Nikko-momi

- Sapin Nikko

- Nikko Tanne

Synonyms

- Abies brachyphylla Maxim.

- Abies firma var. brachyphylla (Maxim.) Bertrand

Infraspecifics

Other taxa in genus

- Abies alba

- Abies amabilis

- Abies × arnoldiana

- Abies balsamea

- Abies beshanzuensis

- Abies borisii-regis

- Abies bracteata

- Abies cephalonica

- Abies × chengii

- Abies chensiensis

- Abies cilicica

- Abies colimensis

- Abies concolor

- Abies delavayi

- Abies densa

- Abies durangensis

- Abies ernestii

- Abies fabri

- Abies fanjingshanensis

- Abies fansipanensis

- Abies fargesii

- Abies ferreana

- Abies firma

- Abies flinckii

- Abies fordei

- Abies forrestii

- Abies forrestii agg. × homolepis

- Abies fraseri

- Abies gamblei

- Abies georgei

- Abies gracilis

- Abies grandis

- Abies guatemalensis

- Abies hickelii

- Abies holophylla

- Abies in Mexico and Mesoamerica

- Abies in the Sino-Himalaya

- Abies × insignis

- Abies kawakamii

- Abies koreana

- Abies koreana Hybrids

- Abies lasiocarpa

- Abies magnifica

- Abies mariesii

- Abies nebrodensis

- Abies nephrolepis

- Abies nordmanniana

- Abies nukiangensis

- Abies numidica

- Abies pindrow

- Abies pinsapo

- Abies procera

- Abies recurvata

- Abies religiosa

- Abies sachalinensis

- Abies salouenensis

- Abies sibirica

- Abies spectabilis

- Abies squamata

- Abies × umbellata

- Abies veitchii

- Abies vejarii

- Abies × vilmorinii

- Abies yuanbaoshanensis

- Abies ziyuanensis

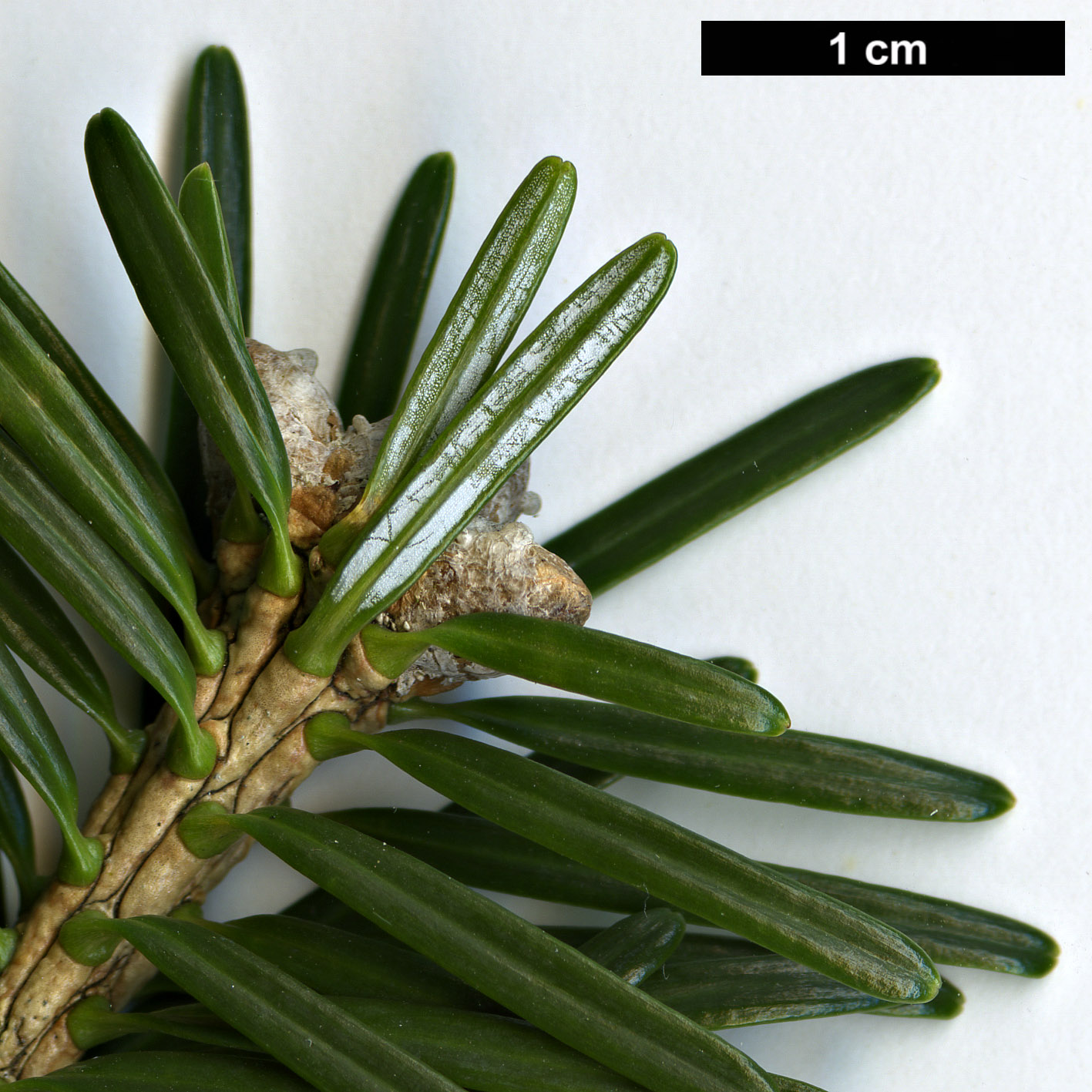

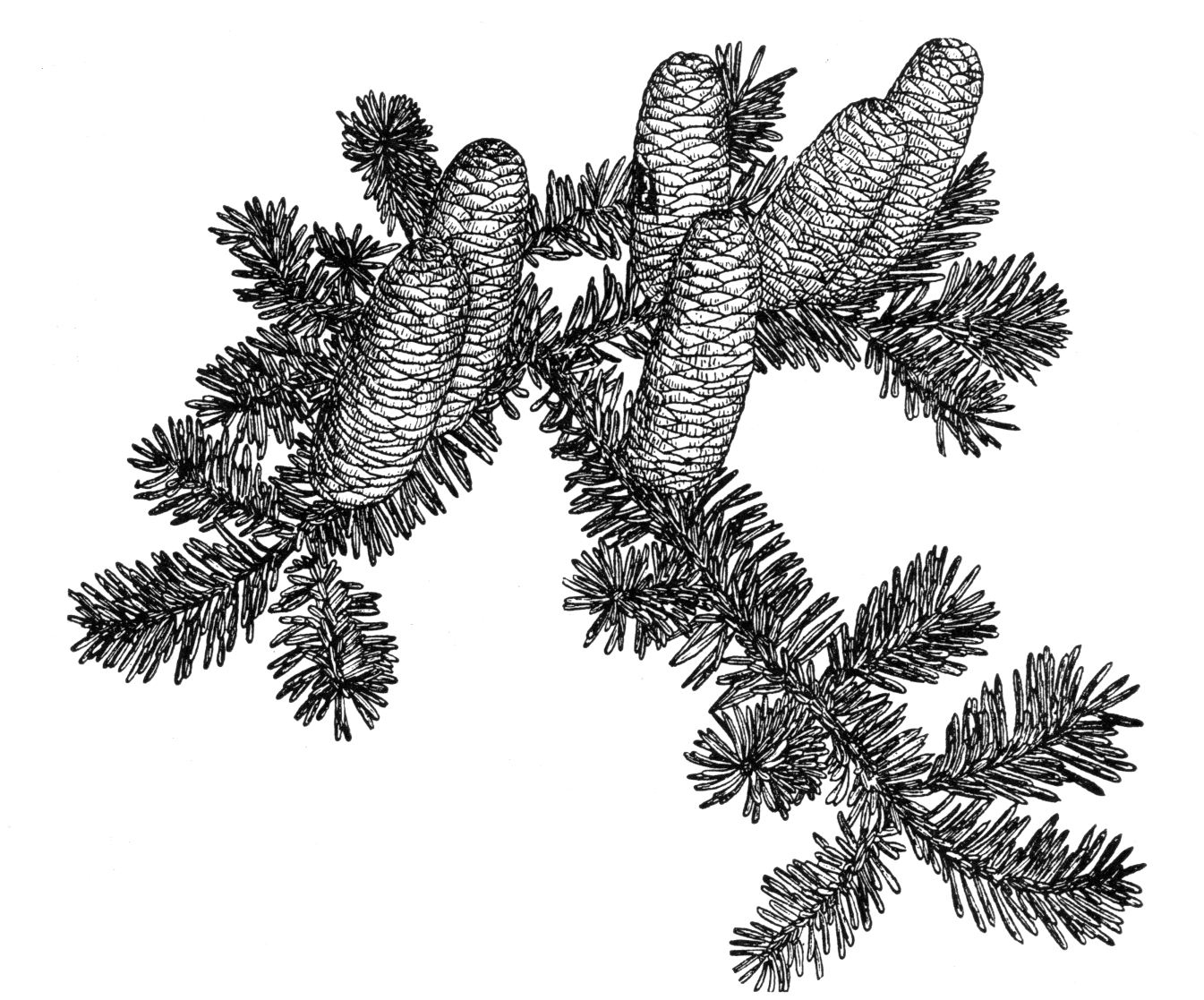

Tree 25–40 m × 1–1.5 m dbh. Crown conical in young trees, becoming broad-pyramidal, old trees becoming flat-topped. Bark of young trees smooth, shedding in fine papery scales, pinkish-grey; in older trees appearing more or less smooth in outline but rough to touch with a distinctive lenticillate pattern, pinkish or yellowish grey-brown, eventually dark grey-brown, rough, breaking into irregular small plates. First order branches long, spreading horizontally or ascending in the upper crown, rarely curved except in the lower crown. Branchlets firm, shining pale buff-brown to whitish-yellow, ridged and deeply grooved, glabrous. Vegetative buds ovoid-conical, 3–5 × 2–4 mm, resinous. Leaves parted above and below the shoots by a ‘V’ (vertical or recurved above the shoot on coning shoots); (1–)1.5–3(–3.5) cm × 2–3.5 mm, curved or twisted at base, deeply grooved and dark green above, occasionally bloomed grey or bluish, apex emarginate, stomata in two silvery-white bands below; crushed needles give a minty aroma. Pollen cones crowded, pendulous, yellowish. Seed cones often clustered, oblong- or conical-cylindrical, 7–10 × 2.5–3.5 cm, apex obtuse, violet or greyish-blue at first, maturing to dark bluish-brown then brown; seed scales flabellate, 1.5–2 × 2.5–3 cm at midcone; bracts included at maturity. (Farjon 2017; Debreczy & Rácz 2011).

Distribution Japan Honshu, Shikoku

Habitat In coniferous or mixed forests in mountains typically at (700–)1000–2000(–2200) m asl. The climate is cool-temperate and humid. At lower elevations and latitudes it is a component of mixed forests, often associating with Fagus crenata, Carpinus spp., Acer spp. and Quercus spp., higher up it associates more commonly with Betula spp., Tsuga diversifolia, Thuja standishii and Pinus densiflora. At higher elevations it most commonly occurs with Abies veitchii and Larix kaempferi which replace it above c. 2000 m; below c. 1000 m it is replaced by A. firma.

USDA Hardiness Zone 4-6

RHS Hardiness Rating H7

Conservation status Near threatened (NT)

Taxonomic note Abies homolepis is a variable species both in the wild and in horticulture. Two varieties have been described: var. umbellata (Mayr) Wilson continues to be recognised in many modern works e.g. Farjon (2017) and Debreczy & Rácz (2011), but recent research supports a long-held view that this taxon represents a natural hybrid between A. homolepis and A. firma (Aizawa & Iwaizumi 2020). It is discussed here as A. × umbellata Mayr emend. Liu. Less commonly accepted is var. tomomi (Bobbink & Atkins) Rehder, described from trees raised from garden-origin seed in the US, it is also discussed under A. × umbellata.

Abies homolepis is a desirable subject in gardens, as it forms an attractive, amenable, and resilient tree. It is modestly tolerant of heat, dry soils, and even air pollution, and though it will not take as much heat as its compatriot A. firma, it is hardier. Its growth is slower than most of the firs commonly grown in our area, and this too can be an advantage.

The story of Nikko Fir’s introduction to the west seems as impenetrable as its native mountains must have to early western visitors to Japan. We know that it was first brought to the attention of western botany by von Siebold, who saw it in gardens around Osaka during the 1820s and later described it with Zuccharini in 1844 (Elwes & Henry 1906–1913). In several early works, including Elwes & Henry’s, it is treated twice: firstly as Siebold and Zuccharini’s ‘imperfectly described’ Abies homolepis, and again under Abies brachyphylla (long since consigned to synonymy). That the same entity was circulating under two different names in the years following its introduction vexed many, and though the muddle has long since been resolved the false dichotomy clouds the early history of this species in gardens.

The earliest date assigned by Elwes & Henry to either name is ‘about 1870’, and many subsequent authors have shrewdly adopted this ambiguity. One notable exception is Alan Mitchell who, with characteristic certitude, gave 1861 (Mitchell 1972), but by 1996 he had joined the Elwes & Henry school of ‘about 1870’, noting: ‘the natural range…was outside the limited area available to collectors in 1860 and James Gould Veitch could not discover it or send seed in 1861, as he did with so many other Japanese conifers’ (Mitchell 1996).

This might be as close as Mitchell ever comes in his writings to admitting an error; ironically, it may have been unnecessary. Jacobson (1996) says it was originally introduced ‘in 1859–60 by Siebold to Holland’, and while he offers no reference for this intriguing snippet it fits with von Siebold’s return to Japan in 1859. It is also tantalisingly close to Mitchell’s original punt of 1861, and it stands to reason that von Siebold’s connections, as a returning visitor, may have proven more effective than Veitch’s.

Whatever the truth – and it is doubtful we will ever know for sure – ‘about 1870’ is certainly when Abies homolepis was first planted in meaningful numbers. It seems to have been simultaneously introduced at about this time both to England and to Holland, and Jacobson (1996) tells us it was in North America by this time, too. In their survey of firs at the Arnold Arboretum Warren & Johnson tell us the first plantings took place there in 1880, and that the species has become an important component of that collection, combining its stately appearance with vigour, general good health, and, curiously, being remarkably wind-firm, none having been uprooted by hurricanes as of 1987 (Warren & Johnson 1988). Jacobson goes on to remark that A. homolepis has become ‘one of the commonest non-native firs planted in North America’ (Jacobson 1996).

It would prove similarly successful in Britain, though perhaps not quite so widely planted. Mitchell (1996) observes that ‘supplies must have been short…for numerous trees are grafts [on A. alba]’ and perhaps this unlikely pairing is one reason few old trees remain. Elwes & Henry made no mention of grafts but observed that the species was seen to be thriving in most parts of England and that it was faster than most other firs at Kew. At that time they could not trace any sizeable trees in Scotland but they supposed that it would surely thrive there. Indeed, by the time Mitchell profiled A. homolepis in Trees of Britain he was able to observe that ‘the biggest and fastest growing’ were all in Scotland (Mitchell 1996). The best on record in 2020 is a 37 m × 1.3 m dbh (measured 2015) tree growing in the abandoned pinetum at the head of Loch Tay in Perthshire. Various others exceeding 30 m grow across Scotland as well as outstanding trees at Wakehurst, West Sussex, and at properties in Surrey, Devon, Powys, and Cumbria (Tree Register 2020). There are many fine specimens throughout Europe, though none are known exceeding 30 m. Several good trees grow in Belgium and the Netherlands, for example at Boswallen Oranje Nassau Oord in the Netherlands there is a tree 27 m × 0.7 m in 2019, while at the Arboretum Poort Bulten a tree was 24.8 m × 0.8 m in 2010. In Belgium there is a tree of 20 m × 0.63 m (in 2011) at the Arboretum Groenendaal (monumentaltrees.com).

Nikko Fir is generally recognisable by its distinctive bark – reddish, rough to the touch, but appearing smooth and rarely breaking into plates – and by its regularly arranged, somewhat stiff green leaves, parted above and below the yellowish shoots by a narrow or wide ‘V’; the leaves may be strongly pectinate or with the uppermost rank more or less upright above the shoot. Leaf length can also vary significantly, but when crushed they give a minty aroma (Mitchell 1972). Despite this variability, the combination of foliage and bark is diagnostic.

Several cultivars are known; nearly all are extreme dwarfs propagated from witches’ brooms and are beyond the scope of this work. A few have been selected for some sort of variegation, but these are mostly very unstable and it would be irresponsible to encourage their proliferation. Few formal Cultivar Groups have been described in Abies, and those that do exist are mostly of obscure origin or else ill defined; A. homolepis Prostrate Group appears to be a recent addition. It was listed by Hatch (2021–2022), though whether it has been published in print (necessary for it to be deemed valid) is unclear. It is tentatively included here.

Prostrate Group

This Cultivar Group covers those dwarf or semi-dwarf plants of spreading-arching habit, ultimately broader than tall. The name has been (invalidly) used as a cultivar name (viz. ‘Prostrata’) since at least 1970, when it was listed by Vermeulen & Son of New Jersey, but this use of a Latin term is impermissible under the ICNCP unless it can be shown to have been in use prior to 1959 (Hatch 2021–2022; Auders & Spicer 2012).