Abies alba

Sponsor

Kindly sponsored by

Sir Henry Angest

Credits

Tom Christian (2021)

Recommended citation

Christian, T. (2021), 'Abies alba' from the website Trees and Shrubs Online (treesandshrubsonline.

Genus

Common Names

- European Silver Fir

- Sapin Pectiné

- Weisstanne

- Abete bianco

Synonyms

- Abies alba subsp. apennina Brullo, Scelsi & Spampinato

- Abies pectinata DC.

Infraspecifics

Other taxa in genus

- Abies amabilis

- Abies × arnoldiana

- Abies balsamea

- Abies beshanzuensis

- Abies borisii-regis

- Abies bracteata

- Abies cephalonica

- Abies × chengii

- Abies chensiensis

- Abies cilicica

- Abies colimensis

- Abies concolor

- Abies delavayi

- Abies densa

- Abies durangensis

- Abies ernestii

- Abies fabri

- Abies fanjingshanensis

- Abies fansipanensis

- Abies fargesii

- Abies ferreana

- Abies firma

- Abies flinckii

- Abies fordei

- Abies forrestii

- Abies forrestii agg. × homolepis

- Abies fraseri

- Abies gamblei

- Abies georgei

- Abies gracilis

- Abies grandis

- Abies guatemalensis

- Abies hickelii

- Abies holophylla

- Abies homolepis

- Abies in Mexico and Mesoamerica

- Abies in the Sino-Himalaya

- Abies × insignis

- Abies kawakamii

- Abies koreana

- Abies koreana Hybrids

- Abies lasiocarpa

- Abies magnifica

- Abies mariesii

- Abies nebrodensis

- Abies nephrolepis

- Abies nordmanniana

- Abies nukiangensis

- Abies numidica

- Abies pindrow

- Abies pinsapo

- Abies procera

- Abies recurvata

- Abies religiosa

- Abies sachalinensis

- Abies salouenensis

- Abies sibirica

- Abies spectabilis

- Abies squamata

- Abies × umbellata

- Abies veitchii

- Abies vejarii

- Abies × vilmorinii

- Abies yuanbaoshanensis

- Abies ziyuanensis

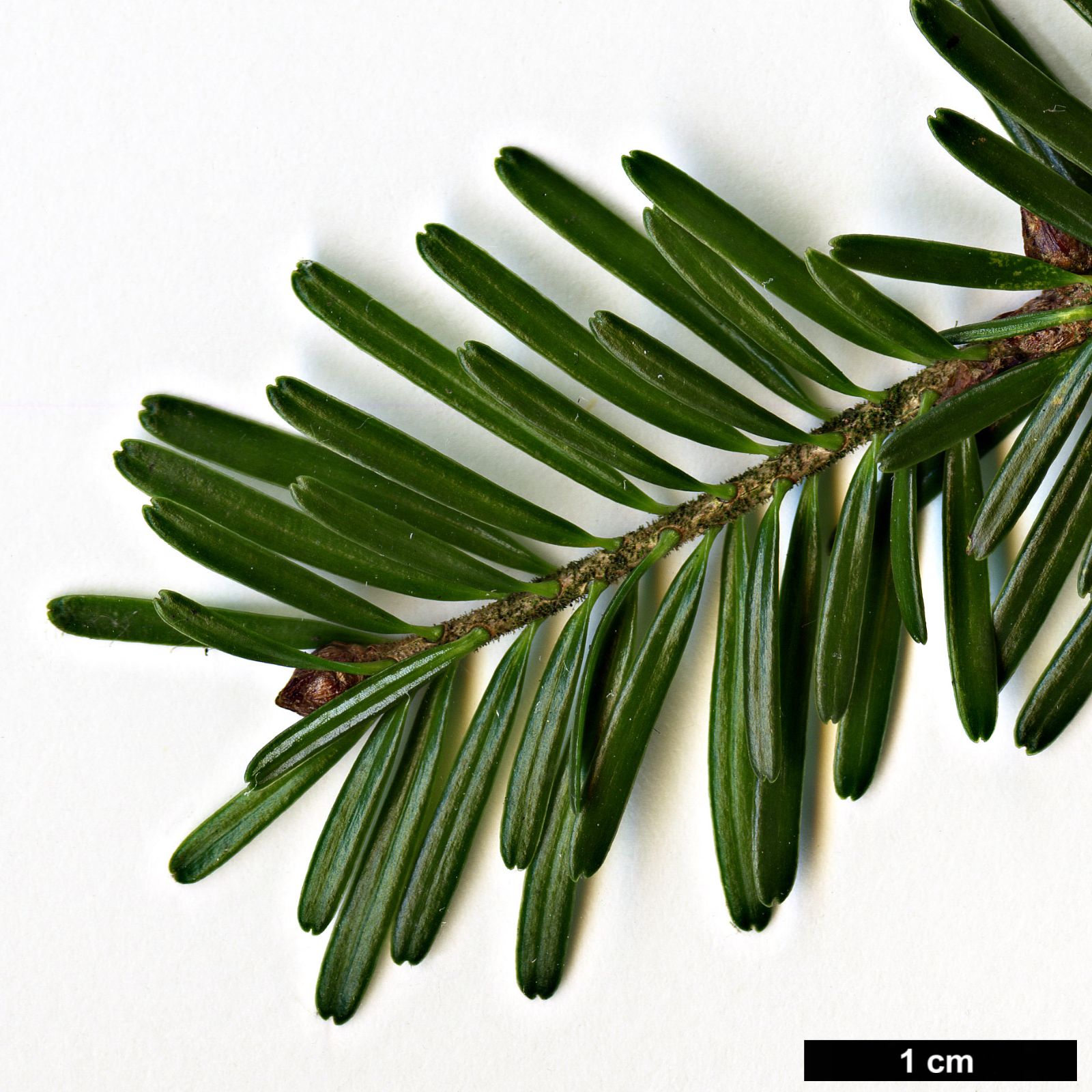

Tree to 60 m tall, 2–2.5 m dbh, exceptionally larger. Crown narrowly pyramidal, neat and symmetrical in young trees, later conical, often ‘stag-headed’ with age. Bark of young trees dull grey-brown, smooth, later pale silvery-grey, becoming scaly and fissured especially in the lower trunk and bole, appearing pink-brown between scales. First order branches erect at first, later horizontal, finally descending. Second order branches slender, spreading more or less horizontally. Branchlets slender, flexible, pale yellow-grey or grey-brown, faintly grooved, variably covered in a pale yellow-brown to blackish pubescence, occasionally ~glabrous especially in vigorous or young trees; cone-bearing shoots stout and rigid. Vegetative buds ovoid or conical, c. 6 × 4 mm, not or only occasionally resinous, usually resinous on cone-bearing branches. Leaves pectinate in two ranks, shorter in the upper ranks, sometimes radial and sparse on vigorous leading shoots, radial or assurgent on cone-bearing shoots, (1.2–)1.5–3(–3.5) cm long, 1.5–2.6 mm wide, base slightly twisted, apex emarginate (obtuse or acute when assurgent), glossy dark green above, dull whitish-green below with two narrow stomatal bands. Pollen cones crowded, 2 cm long, greenish-yellow with purple to red microsporophylls. Seed cones short-pedunculate, narrowly cylindrical, apex obtuse or conical, 10–15(–20) × 3–5(–6) cm, yellowish green at first, sometimes with a red or purple hue, ripening to reddish brown; seed scales cyanthiform, 2.5–3 × 2.5–3 cm at midcone; bracts exserted with triangular or spreading wings, slightly recurved at maturity. (Farjon 2017; Debreczy & Rácz 2011; Tutin et al. 1964).

Distribution Albania Andorra Austria Bosnia and Herzegovina Bulgaria Croatia Czechia France Germany Greece Hungary Italy Kosovo Liechtenstein North Macedonia Montenegro Poland Romania Serbia Slovenia Spain Switzerland Ukraine

Habitat On well-drained soils from 300 (in Bavaria) to 2000 (in the Pyrenees and Apennines) m asl, though most common at 500–1500 m asl. Forming mixed forests primarily with Fagus sylvatica at lower elevations, becoming the first conifer to compete significantly with that species when F. sylvatica becomes less vigorous with altitiude. Co-dominant with Picea abies in coniferous forests of higher elevations, associating locally across its extensive range with a broad range of species including Pinus sylvestris, Larix decidua, and Juniperus communis.

USDA Hardiness Zone 4-7

RHS Hardiness Rating H7

Conservation status Least concern (LC)

Abies alba is the only European fir with an extensive natural range. It occurs from France eastward to the Carpathians and the upper Balkan Peninsula, mostly in mountains but descending into the Black Forest in southern Germany. It has several disjunct outposts including its western limit in the Pyrenees, its eastern limit in the mountains to the north west of the Black Sea, one in Normandy, another in the high mountains of the island of Corsica, and in the Italian Apennine range, too. It is absent from Sardinia, whose mountains are not high enough for it, and it is replaced in Sicily by the narrow endemic A. nebrodensis and in the south-east Balkan peninsula by A. borisii-regis and then by A. cephalonica (Farjon 2017; Tutin et al. 1964). A. alba can be recognised by its pale yellowish-brown or grey shoots with a scattered, dark, relatively long pubescence. On vegetative shoots the needles are generally pectinately arranged, those of the upper-most rank consistently shorter than those of the lower (Mitchell 1972).

It has been a valuable timber tree across its vast range for many hundreds of years, and extensive natural forests continue to be managed for timber production. Its wood is primarily used in general construction or for pulp (Savill et al. 2016). Like the European Larch (Larix decidua) with which it associates locally, European Silver Fir was originally introduced to cultivation outside its native range primarily as a timber tree, though its value as an ornamental did not go unnoticed. It was introduced to Britain in c. 1603 (Mitchell 1972). John Evelyn discussed it in his seminal work Sylva and advised landowners as to its silviculture. Besides its deployment in forestry A. alba quickly became an important component of ornamental plantings on the landscape scale. Many ‘policy woods’ around large Scottish houses were dominated by mixes of A. alba and Fagus sylvatica (somewhat mimicking natural forests in Europe), usually with other species such as Tilia, Castanea, Quercus, and perhaps other conifers such as Larix decidua, Picea abies and native Pinus sylvestris being more minor components. Taxus baccata, Ilex aquifolium and Buxus sempervirens were commonly planted beneath. Some good surviving examples of such woods can still be found in Scotland, for example above the main drive in the grounds of Dunkeld House Hotel, Perthshire, but there are few examples of such woods that haven’t been altered by the introduction, and subsequently the enormous popularity, of the western North American conifers that began to arrive in Britain from the 1830s onward.

The species’ popularity in British forestry would be short lived, as it was found to be a relatively fickle tree to grow well except in the cooler, wetter, western and northern parts of the country. European Larch and Norway Spruce (Picea abies) were soon favoured, being more amenable in forestry and yielding stronger, more versatile timbers, although A. alba continued to be valued for its shade tolerance as a young tree. Increasing incidence of woolly aphid (Adelges nordmanniana) attack meant that by the mid-20th century A. alba was no longer recommended for planting here, though it is interesting to note that it is ‘less susceptible to attack by Fomes (Heterobasidion annosum) than many other conifers’ (Savill et al. 2016). This latter trait renders the species very useful as a rootstock.

A.L. Jacobson notes that A. alba was introduced to cultivation in the USA no later than 1847 – it is tempting to picture the seeds of A. alba and those of its North American counterparts passing mid-Atlantic as the two continents traded flora – and he goes on to note that ‘overall, it is inferior in insect resistance, strength and endurance to A. nordmanniana so has been comparatively little planted in recent years’ (Jacobson 1996). Unlike in the UK and Ireland, where our denuded native tree flora comprises a mere couple of dozen or so species, the rich forests of North America did not particularly need to be supplemented by this new arrival, so it was never planted in quantity and, consequently, did not become such a common feature of the landscape in North America as some of its relatives.

Over the years it has been introduced to cultivation in most of the temperate zone. It may be found in arboreta in northern Europe including Scandinavia, in Russia and in Russia’s Far East, in temperate east Asia and in Australasia. Like nearly all firs it favours steep slopes, good soils, and a cool, moist climate. Bean (1976) noted that it ‘refuses to grow in the hot, dry, Lower Thames Valley, and does not thrive in many low-lying and frosty parts of the south of England’. The last few years have seen renewed interest in planting this species in the south of England as an ornamental, perhaps in response to the dwindling number of old trees, and although handsome and vigorous young trees may be seen in collections such as Kew and Bedgebury it seems unlikely that these will remain so for very long. These days the greatest concentration of fine trees in the UK and Ireland is to be found in Scotland, although impressive examples may also be seen in the valleys of the Lake District, in Wales, and in parts of the West Country, too. It has been widely planted across the island of Ireland where it has been known to reach 50 m height. The tallest extant tree in the UK was 53 m in 2013. It grows on a private estate in Highland Perthshire, on rich alluvial soils on a slope on the edge of the Tay valley, sheltered by a high hill rising steeply to the west (Tree Register 2020). A truly remarkable tree, its status confirmed as such by Thomas Pakenham in Meetings with Remarkable Trees, grows in the woodland garden at Ardkinglas, Argyll, Scotland. This ‘monster’ Silver Fir, so-called, soon divides from its single bole into four giant, ascending stems that would each be impressive as an individual tree in its own right. One of the oldest extant trees of confirmed planting date grows at Dawyck Botanic Garden, Peeblesshire, where it was planted in 1680 (Rodger, Stokes & Ogilvie 2006).

Although many of the forests where it grows naturally have a long history of management, there are various locations where it has escaped interference and where large trees can still be found. Examples approaching 60 m tall have been recorded in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Germany, Slovakia, and Switzerland. One of the most notable examples is a tree in the Biogradska Gora National Park, Montenegro. Discovered in 2019, it measured just shy of 60 m tall and 2.27 m dbh, making it both the tallest and largest single-stemmed tree on record (monumentaltrees.com).

With a native range taking in many countries with long-standing horticultural traditions, and a long history of cultivation in others, there are a great many cultivars of A. alba. The overwhelming majority are dwarfs, here taken to mean remaining <3 m in ten years, and most are considerably smaller than this, remaining compact shrubs of <1 m in the same timeframe, varying slightly in shape and habit. Those that genuinely distinguish themselves in one way or another are discussed below, while the myriad witches’ brooms and other extreme dwarf look-alikes are listed together under ‘Dwarf Cultivars’.

'Compacta'

‘Compacta’ is a curious selection, and one of the first fir cultivars to be raised in the USA; it was selected at the Parsons Nursery, New York, c. 1885. It forms a semi-dwarf tree, or large shrub, ultimately wider than tall, with many densely set near-fastigiate branches. The needles are reportedly glossier than the typical species (Hatch 2021–2022).

Dwarf Cultivars

With a natural distribution dissecting the European continent A. alba has long attracted the attention of conifer specialists in areas with long-standing horticultural traditions. Consequently, many dwarfs have been raised or selected, from gardens and from the wild, especially in central and eastern Europe where the species forms vast forests. Several of these selections are quite old, but an explosion of new names in recent decades – many traceable to Czechia – reflects the intense interest in such forms that continues to the present day. Indeed, new selections are emerging all the time, but so great are these in number now that with each new name their meaning is, ironically, diluted. This non-exhaustive list of A. alba dwarfs tries to include all those that are aesthetically unique, but the majority are remarkably alike, especially those described as extreme dwarfs. All the cultivars listed here typically remain <3 m after ten years, whilst those very miniature selections referred to as extreme dwarfs, often from witches’ brooms, typically remain below 1 m after ten years.

- ‘Argan’ An extreme dwarf, ultimately broader than tall. Raised from a witches’ broom by G. Eschrich.

- ‘Aurea’ An old selection first reported in 1866, it has new growth bright golden-yellow, soon green but with sporadic yellow branchlets retained.

- ‘Barabits Spreading’ (‘Barabits Spreader’) Raised by the Hungarian firm of Barabits in 1965, this selection has a broad-pyramidal habit at first, becoming globose after many years.

- ‘Brevifolia’ A selection with very short leaves, but of typical width. Raised at the Sénéclauze Nursery, France, in 1861.

- ‘Brinar’ An exceptionally slow-growing, extreme dwarf, which can remain as little as 30 cm tall after ten years.

- ‘Bystřička’ A minute selection propagated from a witches’ broom found in Czechia in 1996.

- ‘Compacta’ (‘Nana Compacta’) A selection of very dense branching and globose habit, discovered by the Parsons Nursery, NY, USA, c. 1885.

- ‘Elegans’ An obscure cultivar that appeared in France during the 1860s. It is described as bushy, with leaves ‘split at the tip’.

- ‘Havel’ An extreme dwarf raised in 2001 by the eponymous nursery in Czechia.

- ‘Hedge’ (‘Hiedge’) An extreme dwarf raised in the Netherlands in 2001. It forms a low mound with a central depression and short leaves.

- ‘Hochstuckli’ An extreme dwarf raised in Germany by J. Kohout during the 1990s.

- ‘Holden Arboretum WB’ Propagated from a witches’ broom at the famous arboretum in Ohio.

- ‘Ibergeregg’ (‘Iberegg’) Distinguished from so many other selections listed here by its narrow, erect habit, growing to 1 × 0.4 m in ten years. Presumably raised in Oregon, USA, in the early 2000s.

- ‘Kamenná Lhota’ Another extreme dwarf of Czech origin, this time raised raised in 2007 by Szuma.

- ‘King’s Dwarf’ An upright, conical dwarf growing to 1.5 × 0.5 m in ten years. Raised by the King and Paton Nursery in Scotland prior to 1983.

- ‘Kladsko’ (‘Kladská’) An extreme dwarf of Czech origin, forming a mound 30 cm tall and broad after ten years.

- ‘Kroc’ An extreme dwarf of moderate growth, ultimately wider than tall.

- ‘Krymlov’ Reportedly differing from so many other witches’ brooms in the pale green colour of its leaves. Raised in Czechia in 1996.

- ‘Laja’ An extreme dwarf growing wider than tall.

- ‘Lucja’ An extreme dwarf of very slow growth with very dark green leaves.

- ‘Maraton’ An extreme dwarf of spreading habit first listed by Edwin Smits nursery in the Netherlands in 2009.

- ‘Microphylla’ An unusual selection of relatively fast growth, to 1.5 × 1 m in ten years, but ultimately wider than tall. The branchlets are short and very dense, and the leaves are remarkably narrow.

- ‘Mladá Boleslav’ (‘Veselý’; ‘Visely’) A globose dwarf of modest growth, to 60 × 60 cm in ten years. Found in Czechia and introduced to cultivation by the Horstmann nurseries in Germany in 1992

- ‘Nana’ A globose plant with dark green leaves first listed by the English firm Knight & Perry in 1850.

- ‘Pygmy’ An extreme dwarf of unknown origin which first appeared in a Dutch catalogue in 1990.

- ‘Scarabantia’ An extreme dwarf put into commerce by the Horstmann nurseries in Germany in 1992. To 40 × 80 cm in ten years.

- ‘Schwarzwald’ (‘Badenweiler’) Discovered prior to 1978 as a witches’ broom at Badenweiler in Schwarzwald, Germany. It forms an extreme dwarf of irregular habit.

- ‘Šejna’ An extreme dwarf of globose habit, to 40 × 40 cm in ten years.

- ‘Strĕla’ An extreme dwarf of globose habit listed by the Edwin Smits Nursery in the Netherlands in 2009.

- ‘Svartá Hora’ An extreme dwarf of very slow growth, as little as 1–2 cm per year. Raised in Czechia before 2009.

- ‘Zahaj’ A flat-topped extreme dwarf, to 30 × 50 cm in ten years.

'Fastigiata'

There is considerable confusion around the historic use of the names ‘Columnaris’, ‘Fastigiata’, ‘Pyramidalis’, and ‘Stricta’. Auders & Spicer (2012) discuss the latter three together, and suggest that these have been applied, sometimes in combination (e.g. ‘Pyramidalis Stricta’) to two distinct clones, which they treat as ‘Fastigiata’ and ‘Pyramidalis’. (They also treat ‘Columnaris’ as distinct). The names, at least, have distinct origins: ‘Fastigiata’ was introduced in France by Sénéclauze c. 1846; ‘Pyramidalis’ is of German origin but first entered commerce in Britain, possibly via the Lawson nursery, c. 1851; and ‘Columnaris’ was found wild in France and described by Carrière in 1859 (Jacobson 1996). Within just a few years confusion was rife in literature (Auders & Spicer 2012). ‘Fastigiata’ is apparently of slightly slower growth than ‘Pyramidalis’, but beyond this there is no useful distinction, and it is very likely that the three have been confused in nurseries for well over a century now, with comporable seed-raised forms assigned to one or the other at random. A Fastigiata Group, to cover all such forms, would solve the problem but upset the purists.

'Green Spiral'

A remarkable selection, forming a ‘wobbly’, loosely twisting trunk rising to several meters, from which short, curving, somewhat pendulous branches are irregularly borne. The leaves are densely set on the shoots and shorter than in the type (Auders & Spicer 2012). Of obscure origin, ‘Green Spiral’ was first spotted growing in the Secrest Arboretum in Ohio in 1916. The plant had been obtained from Biltmore Nursery in North Carolina labelled A. alba ‘Tortuosa’; it is probably a sport of this cultivar. It is relatively slow, typically 2.5 m in ten years, but Hatch gives an ultimate height of c. 10 m (Hatch 2021–2022).

'Pendula'

Synonyms / alternative names

Abies alba f. pendula (Carr.) Aschers. & Graebn.

Bean (1976) notes that pendulous examples of A. alba have been reported from wild forests in several parts of its range, but this clone is often described as one of the best truly weeping firs in existence, despite having been selected as long ago as 1835 when it was found at the Godefroy Nursery in France. It quickly became popular, arriving in Britain soon after its discovery, and in North America by 1891 (Jacobson 1996). The Tree Register reports a remarkable, if slightly gaunt 17 m tree in a private garden in Plymouth, UK (Tree Register 2021) whilst Larry Hatch heaps well-deserved praise on several examples at Gettysburg National Cemetery in Pennsylvania (Hatch 2021–2022). It deserves to be more widely planted.

'Tortuosa'

A very old cultivar raised in Germany c. 1835, ‘Tortuosa’ is a semi-dwarf tree of compact, irregular, contorted habit. Slow to start, it can be vigorous once established. The main stem is twisted and may need to be staked to grow upright; from this contorted branches are borne, themselves bearing twisted and often with pendulous branchlets – even the leaves can be twisted (Auders & Spicer 2012).

'Umbraculifera'

A selection found sometime before 1868 in a forest on the River Loire in France. It has an umbrella-like crown with spreading branches. These are densely set on the tree, quite short, thick, ascending when young but later nodding (Debreczy & Rácz 2011).

'Virgata'

Selected from the wild in Czechia’s Bohemian Forest, c. 1879, ‘Virgata’ has first-order branches that hang almost vertically from the central leader. Auders & Spicer describe it as ‘broad’ but it may be more upright in a forest or arboretum setting (Auders & Spicer 2012).