Magnolia denudata

Sponsor

Kindly sponsored by

The Roy Overland Charitable Trust

Credits

Julian Sutton (2022)

Recommended citation

Sutton, J. (2022), 'Magnolia denudata' from the website Trees and Shrubs Online (treesandshrubsonline.

Genus

- Magnolia

- Section Yulania

Common Names

- Yulan

- Lily Tree

- Slender Magnolia

- yu lan

Synonyms

- Magnolia conspicua Salisb.

- Magnolia heptapeta (Buc'hoz) Dandy

- Magnolia yulan Desf.

- Yulania denudata (Desr.) D.L. Fu

Infraspecifics

Other taxa in genus

- Magnolia acuminata

- Magnolia × alba

- Magnolia amabilis

- Magnolia amoena

- Magnolia aromatica

- Magnolia biondii

- Magnolia × brooklynensis

- Magnolia campbellii

- Magnolia cathcartii

- Magnolia cavaleriei

- Magnolia caveana

- Magnolia champaca

- Magnolia changhungtana

- Magnolia chapensis

- Magnolia compressa

- Magnolia conifera

- Magnolia Cultivars A

- Magnolia Cultivars B

- Magnolia Cultivars C

- Magnolia Cultivars D

- Magnolia Cultivars E

- Magnolia Cultivars F

- Magnolia Cultivars G

- Magnolia Cultivars H–I

- Magnolia Cultivars J

- Magnolia Cultivars K

- Magnolia Cultivars L

- Magnolia Cultivars M

- Magnolia Cultivars N–O

- Magnolia Cultivars P

- Magnolia Cultivars Q–R

- Magnolia Cultivars S

- Magnolia Cultivars T

- Magnolia Cultivars U–V

- Magnolia Cultivars W–Z

- Magnolia cylindrica

- Magnolia dandyi

- Magnolia dawsoniana

- Magnolia de Vos and Kosar hybrids

- Magnolia decidua

- Magnolia delavayi

- Magnolia doltsopa

- Magnolia duclouxii

- Magnolia ernestii

- Magnolia figo

- Magnolia floribunda

- Magnolia × foggii

- Magnolia fordiana

- Magnolia foveolata

- Magnolia fraseri

- Magnolia fulva

- Magnolia globosa

- Magnolia × gotoburgensis

- Magnolia grandiflora

- Magnolia grandis

- Magnolia Gresham hybrids

- Magnolia guangdongensis

- Magnolia hookeri

- Magnolia insignis

- Magnolia Jury hybrids

- Magnolia × kewensis

- Magnolia kobus

- Magnolia kwangtungensis

- Magnolia laevifolia

- Magnolia lanuginosa

- Magnolia leveilleana

- Magnolia liliiflora

- Magnolia × loebneri

- Magnolia lotungensis

- Magnolia macclurei

- Magnolia macrophylla

- Magnolia martini

- Magnolia maudiae

- Magnolia nitida

- Magnolia obovata

- Magnolia officinalis

- Magnolia opipara

- Magnolia × proctoriana

- Magnolia × pruhoniciana

- Magnolia rostrata

- Magnolia salicifolia

- Magnolia sapaensis

- Magnolia sargentiana

- Magnolia sieboldii

- Magnolia sinensis

- Magnolia sinica

- Magnolia sinostellata

- Magnolia × soulangeana

- Magnolia sprengeri

- Magnolia stellata

- Magnolia tamaulipana

- Magnolia × thomsoniana

- Magnolia tripetala

- Magnolia × veitchii

- Magnolia virginiana

- Magnolia × wieseneri

- Magnolia wilsonii

- Magnolia xinganensis

- Magnolia yunnanensis

- Magnolia yuyuanensis

- Magnolia zenii

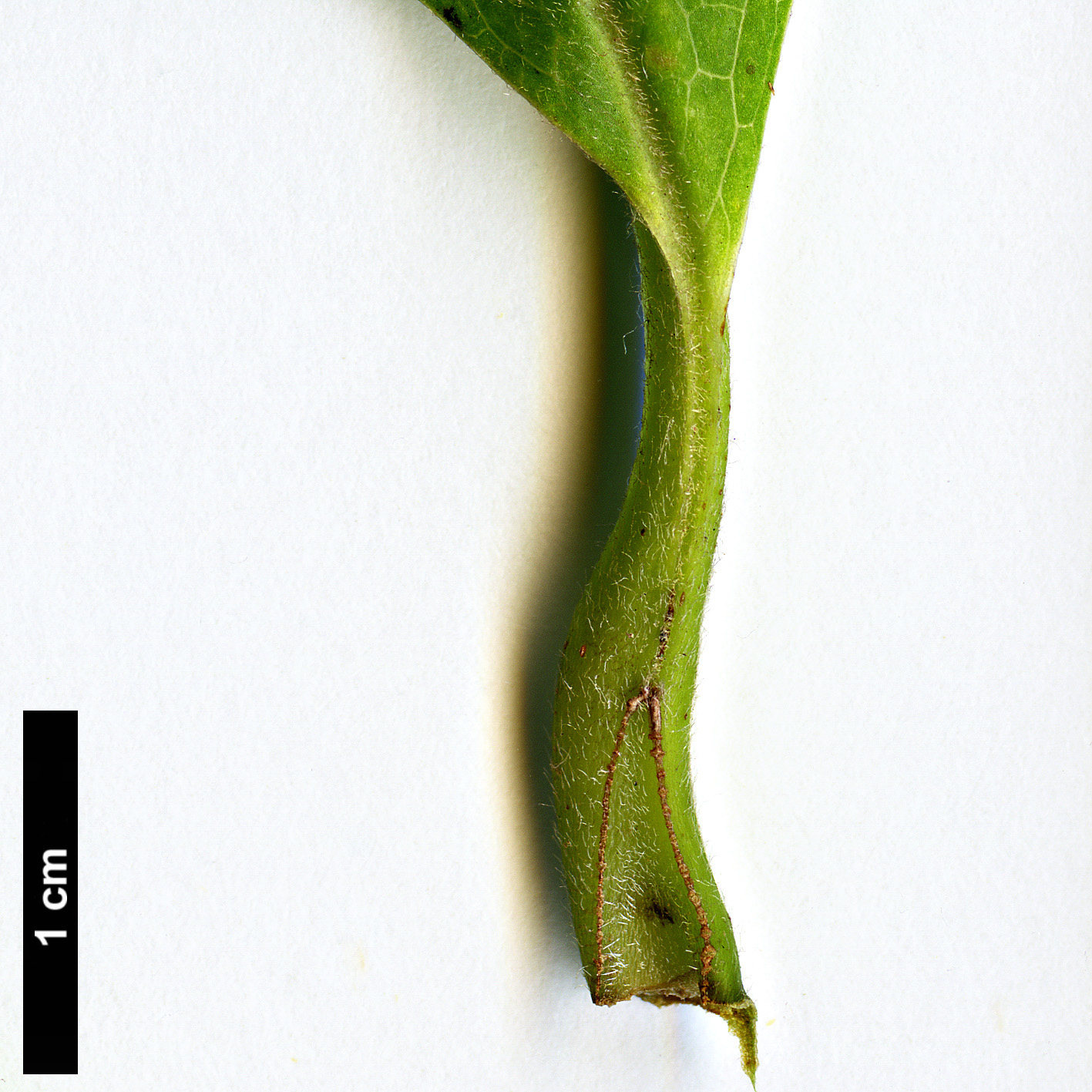

Deciduous tree to 25 m tall and 1 m dbh. Bark grey, fissured, sometimes peeling off in plates. Winter buds and peduncles with long, dense, yellowish silky hairs. Branches spreading, forming a broad crown; branchlets brown, 3–7 mm in diameter, with silky hairs at first, becoming glabrous. Leaf blade obovate or obovate-elliptic, but basal leaves elliptic, 10–15(–18) × 6–10(–12) cm, papery, gradually narrowing from middle toward base; lower surface pale green and villous along veins; upper surface deep green, hairy when young, later only on major veins; secondary veins 8–10 on each side of midvein, reticulate veins conspicuous; apex broadly rounded, truncate, or slightly emarginate. Petiole 1–2.5 cm, villous, narrowly furrowed above; stipular scar ¼–⅓ as long as petiole. Peduncle significantly enlarged, with long, dense, yellowish silky hairs. Flower buds ovoid. Flowers appearing before leaves, 10–16 cm across, erect, fragrant. Tepals 9, white (to yellow and pink in some selected forms), oblong-obovate, 6–8(–10) × 2.5–4.5(–6.5) cm, subequal, base usually tinged pink or purple. Stamens 7–12 mm; connective ~5 mm wide, exserted and forming a mucro; anthers 6–7 mm, dehiscing laterally. Gynoecium pale green, cylindric, 2–2.5 cm, glabrous; ovaries narrowly ovoid, 3–4 mm; styles conical, c. 4 mm. Fruit cylindric but in cultivation often curved because of carpels partly undeveloped, 12–15 × 3.5–5 cm; mature carpels brown, thickly woody, white lenticellate. Seeds cordate, ~9 × 10 mm, laterally compressed; testa red; endotesta black. Flowering February–March, fruiting August–September. Tetraploid or hexaploid, 2n =76, 114. (Xia, Liu & Nooteboom 2008; Chen & Nooteboom 1993; Spongberg 1976).

Distribution China Anhui, Chongqing, N Guangdong, Guizhou, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, Shaanxi, Yunnan, Zhejiang.

Habitat Forests, 500–1000 m.

USDA Hardiness Zone 5-9

RHS Hardiness Rating H6

Awards AGM

Conservation status Least concern (LC)

Taxonomic note Synonymy in this species is complicated (see Chen & Nooteboom 1993; Meyer & McClintock 1987). The debate hinges on whether the older synonym M. heptapeta (based on Lassonia heptapeta Buc’hoz) should be rejected since its type was a mere artistic impression of the species (just the same problems apply to M. liliiflora q.v.). We follow Meyer & McClintock (1987), Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (2021), Figlar (2012) and most contemporary usage in accepting the more familiar M. denudata.

This member of Section Yulania can look superb in the garden as a small, rounded tree covered in fragrant goblet-shaped white flowers in early spring, decisively before leaf emergence (hence the specific epithet – ‘stripped bare’). although this was not always seen as an advantage. The author (unattributed, but probably John Sims) of the description published in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine in 1814 (t. 1621) thought ‘it is far less agreeable than the Magnolia grandiflora, whose beautiful blossoms are beautifully contrasted, by being embosomed in large shining leaves.’ Intrinsically a hardy tree, it has one great fault: the flowers are easily browned by even quite slight frosts, which is highly disfiguring.

It has a long history in cultivation, grown in Chinese temple gardens since the Tang Dynasty (618–907) and soon spreading to Japan (Treseder 1978). George Forrest waxed lyrical over the sight of an avenue of well grown specimens in full flower at a large house in W Yunnan (fide Savage 1974). It is today planted as a street tree in some Chinese cities. Introduction to the West was almost certainly from Asiatic cultivation, and is usually credited to the British botanical explorer and establishment insider Sir Joseph Banks, in the 1780s (Gardiner 2000). Banks himself collected many living plants on his travels (most famously with James Cook) but later orchestrated collecting efforts by others. It was long an uncommon tree in Britain, with a few famous specimens in the London area, becoming commoner when Dutch nurseries began to propagate it by grafting on M. × soulangeana (Bean 1981). It was in North American commerce by 1854 (Jacobson 1996). This clone remains one of the best, with large pure white flowers and a delicious lemony fragrance. It ought to be distinguished by a cultivar name.

Introductions from China have clearly continued, but no recent collections stand out. Their status is often clouded by possible misidentification, and the possibility of plants cultivated in China being collected as if they were wild. For example, NACPEC 02058 (Shaanxi 2002) has proved not to be M. denudata, rather perhaps M. biondii, while some other siupposedly wild collections received by the US National Arboretum were from areas where the species has not been recorded as a wild plant (US National Arboretum 2022).

In cultivation M. denudata makes a multi-stemmed shrub or broad, spreading, small tree. Quite variable in vigour, some 100-year-old specimens may only have a height and span of around 9 m. Much taller specimens are certainly exceptional, for example trees at the Valley Gardens, Windsor Great Park (14.5 m × 161 cm, 2021) and Pencarrow, Cornwall (15 m × 136 cm, 2016 – The Tree Register 2021). It is best grown in sun or light, dappled shade. A rich, moisture retentive, somewhat acidic soil is ideal, although it will tolerate alkaline soil given adequate summer moisture.

M. denudata flowers well from a young age. Flowers vary in size and colour. Seedlings in Chinese cultivation range from the typical pure white to yellow or pink, by way of ivory and blush (M. Robinson pers. comm. to J. Gardiner, 1997). Some of this range is seen in Western cultivars. However, the status of these colour forms is cast in doubt by the discovery that the well established ‘Forrest’s Pink’ (pink tepals, darker at base) and ‘Purple Eye’ (white with purple bases) are respectively heptaploid and octaploid, and hence almost certainly hybrids (unpublished flow cytometry data of R. Olsen & S. Lura (2013) cited by US National Arboretum 2022 and Lobdell 2021). We continue provisionally to list other pigmented cultivars here in the absence of direct evidence. Again controversially, this time on the gastronomic front, tepals of M. denudata are considered a delicacy by some: dipped in flour and fried in oil until crisp, they have a slightly sweet taste (Gardiner 2000).

In Europe it is widely grown from Britain, Ireland and France east to Germany and Poland, where its hardiness is limited, with damage to buds and branchlets in severe winters (Anisko & Czekalski 1991). In North America it proves ‘amazingly adaptable’ (Dirr 2009) growing on both seaboards from Maine to Florida and Washington to S California, as well as in the Great Lakes area; around St Louis, MO it is marginal (Missouri Botanical Garden 2021).

M. denudata is a parent of the important hybrids M. × soulangeana and M. × veitchii, also more recently of ‘Elizabeth’ and other yellow flowered hybrids.

'Gere'

A beautiful ivory-white selection flowering with the last M. × soulangeana cultivars. Selected by Joe McDaniel in an Urbana, IL cemetery before 1987, and given the name on the nearest tombstone.

'Minrose'

Synonyms / alternative names

Magnolia denudata FESTIROSE®

Tepals pink with a darker midline outside. Selected 1998 by Pépinières Minier, France but only recently mass-marketed in Europe. Its status as unhybridized M. denudata must be regarded as provisional.

'Sawada's Cream'

Tepals bright butter yellow on opening, fading to creamy white. Setting seed readily, it has been used by Phil Savage in his breeding programmes, and was obtained from Camellia specialist Kosaku Sawada (d. 1968) of Overlook Nursery, Mobile, AL.

'Sawada's Pink'

All details as for ‘Sawada’s Cream’, except that there is pink in the opening flowers. Sawada raised it from Japanese seed listed as M. denudata var. purpurascens.

'Swarthmore Sentinel'

Narrow upright habit; upright cup-shaped white flowers with 12 tepals which splay open as the flower ages. The original tree was a seedling given in 1987 to the Scott Arboretum of Swarthmore College, PA by J.C. Raulston, who had obtained seed from Beijing Botanic Garden.

var. purpurascens (Maxim.) Rehd. & Wils., in part.

Synonyms

Magnolia conspicua var. purpurascens Maxim.

This name has been used for examples with tepals rosy-purple on the outside, originally described from plants cultivated in Japan but also occuring in the wild in China. It should not be confused with M. sprengeri, the pink-flowered forms of which were originally identified as M. denudata var. purpurascens by Rehder and Wilson (Bean 1981). It seems scarcely to deserve varietal status, and the name is rarely seen nowadays.