Magnolia campbellii

Sponsor

Kindly sponsored by

The Roy Overland Charitable Trust

Credits

Julian Sutton (2022)

Recommended citation

Sutton, J. (2022), 'Magnolia campbellii' from the website Trees and Shrubs Online (treesandshrubsonline.

Genus

- Magnolia

- Section Yulania

Common Names

- Campbell's Magnolia

- dian zang yu lan

Synonyms

- Magnolia mollicomata W.W. Sm.

- Magnolia campbellii var. mollicomata (W.W. Sm.) F.S. Ward

- Magnolia campbellii subsp. mollicomata (W.W. Sm.) G.H. Johnstone

- Yulania campbellii (Hook. f. & Thomson) D.L. Fu

Infraspecifics

Other taxa in genus

- Magnolia acuminata

- Magnolia × alba

- Magnolia amabilis

- Magnolia amoena

- Magnolia aromatica

- Magnolia biondii

- Magnolia × brooklynensis

- Magnolia cathcartii

- Magnolia cavaleriei

- Magnolia caveana

- Magnolia champaca

- Magnolia changhungtana

- Magnolia chapensis

- Magnolia compressa

- Magnolia conifera

- Magnolia Cultivars A

- Magnolia Cultivars B

- Magnolia Cultivars C

- Magnolia Cultivars D

- Magnolia Cultivars E

- Magnolia Cultivars F

- Magnolia Cultivars G

- Magnolia Cultivars H–I

- Magnolia Cultivars J

- Magnolia Cultivars K

- Magnolia Cultivars L

- Magnolia Cultivars M

- Magnolia Cultivars N–O

- Magnolia Cultivars P

- Magnolia Cultivars Q–R

- Magnolia Cultivars S

- Magnolia Cultivars T

- Magnolia Cultivars U–V

- Magnolia Cultivars W–Z

- Magnolia cylindrica

- Magnolia dandyi

- Magnolia dawsoniana

- Magnolia de Vos and Kosar hybrids

- Magnolia decidua

- Magnolia delavayi

- Magnolia denudata

- Magnolia doltsopa

- Magnolia duclouxii

- Magnolia ernestii

- Magnolia figo

- Magnolia floribunda

- Magnolia × foggii

- Magnolia fordiana

- Magnolia foveolata

- Magnolia fraseri

- Magnolia fulva

- Magnolia globosa

- Magnolia × gotoburgensis

- Magnolia grandiflora

- Magnolia grandis

- Magnolia Gresham hybrids

- Magnolia guangdongensis

- Magnolia hookeri

- Magnolia insignis

- Magnolia Jury hybrids

- Magnolia × kewensis

- Magnolia kobus

- Magnolia kwangtungensis

- Magnolia laevifolia

- Magnolia lanuginosa

- Magnolia leveilleana

- Magnolia liliiflora

- Magnolia × loebneri

- Magnolia lotungensis

- Magnolia macclurei

- Magnolia macrophylla

- Magnolia martini

- Magnolia maudiae

- Magnolia nitida

- Magnolia obovata

- Magnolia officinalis

- Magnolia opipara

- Magnolia × proctoriana

- Magnolia × pruhoniciana

- Magnolia rostrata

- Magnolia salicifolia

- Magnolia sapaensis

- Magnolia sargentiana

- Magnolia sieboldii

- Magnolia sinensis

- Magnolia sinica

- Magnolia sinostellata

- Magnolia × soulangeana

- Magnolia sprengeri

- Magnolia stellata

- Magnolia tamaulipana

- Magnolia × thomsoniana

- Magnolia tripetala

- Magnolia × veitchii

- Magnolia virginiana

- Magnolia × wieseneri

- Magnolia wilsonii

- Magnolia xinganensis

- Magnolia yunnanensis

- Magnolia yuyuanensis

- Magnolia zenii

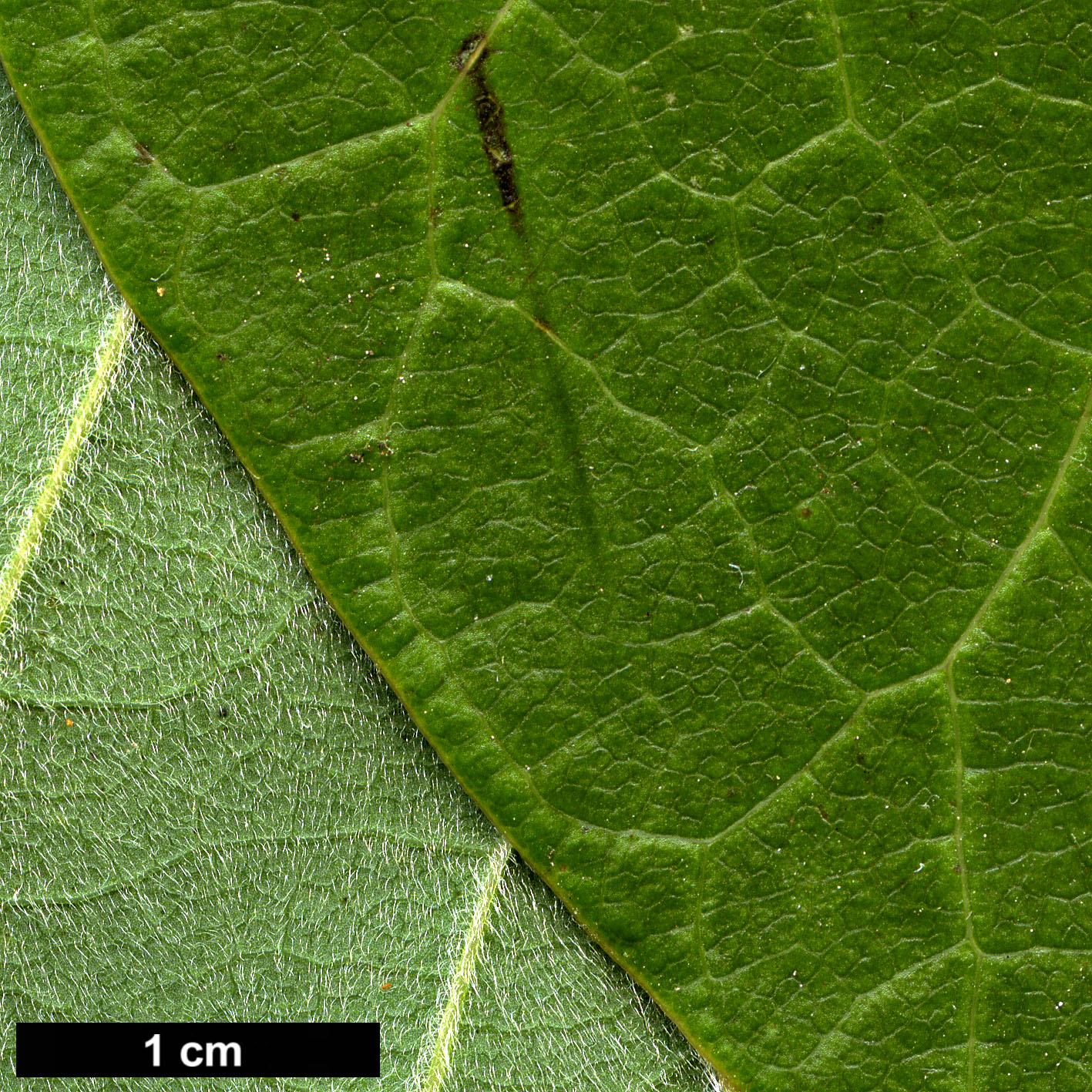

Deciduous tree to 30 m. Bark grey-brown. Branchlets glabrous, yellowish green when young, becoming reddish brown. Leaf blade elliptic, oblong-ovate, or broadly obovate, 10–23(–33) × 4.5–10(–14) cm, papery; lower surface grey-green with white appressed hairs; upper surface deep green, glabrous; midvein and secondary veins with long, appressed silky hairs; secondary veins 12–16 on each side of midvein; base rounded to broadly cuneate and usually unequal; apex acute to shortly acuminate. Petiole 1–5 cm, pilose; stipular scar short and small. Peduncle thick and strong, ~2 cm, glabrous or slightly pilose. Flower buds ovoid, ~2.5 cm, with pale yellow silky hairs. Flowers appearing before leaves, 15–25(–35) cm across, slightly fragrant. Tepals 12–16, dark red, pink, or white, obovate-spoon-shaped to oblong-ovate, 6–14 × 4–6 cm, base gradually narrowed and forming a claw; outer 3 spreading, reflexed, or pendulous; tepals of innermost whorl broadly ovate to suborbicular, 8–10 × 4–6 cm, erect, surrounding stamens and gynoecium. Stamens 1–3 cm; filaments purplish red. Gynoecium green, 2–3 cm; stigmas red. Fruiting peduncle thick and strong, 1–1.5 cm in diameter, glabrous. Fruit purplish red turning brown, terete, 11–20 × 2.5–3 cm, erect at first, then pendulous; mature carpels firmly connate, thin, dehiscing into 2 valves along dorsal sutures. Seeds cordate, 1–1.2 × 0.8–1 cm, laterally flat. Flowering March–May, fruiting June–July (China). Hexaploid 2n=114. (Xia, Liu & Nooteboom 2008).

Distribution Bhutan Myanmar N China S Xizang, NW Yunnan India NE (Assam, Sikkim) Nepal

Habitat Forests; 2500–3500 m in China.

USDA Hardiness Zone 7-9

RHS Hardiness Rating H4

Conservation status Least concern (LC)

In its best forms this is a truly spectacular flowering tree. Potentially very tall and widely spreading, its huge flowers borne on bare branches alarmingly early in spring are typically a vivid rose-pink. While it grows well in mild, maritime areas such as southern and western Britain, this is a Hell’s Angel among magnolias, its fat hairy buds racing down the middle of the road to spring, and if frost is coming the other way it will not be the one to swerve. The high risk of buds and flowers being disfigured or effectively destroyed makes a good flowering season even more special, but also makes other, later flowering tree magnolias a less risky bet for all but the ambitious, optimistic gardener who has plenty of space and time to wait.

Among the larger, decisively tree-forming species of Section Yulania, M. sprengeri and M. campbellii are distinguished from M. dawsoniana and M. sargentiana by their upright rather than horizontal or drooping flowers. M. campbellii differs from the somewhat smaller M. sprengeri in its more or less ovate (as opposed to more or less obovate) leaves, and in its clawed tepals.

Magnolia campbellii was first described scientifically from the western end of its range, in NE India (Hooker & Thomson 1855), where it had brought itself to the attention of several colonial-era collectors. The specific epithet commemorates Archibald Campbell, a British East India Company official instrumental in getting Hooker and Thomson into Sikkim on their expedition of 1849–50. The many introductions to cultivation in Europe (especially Britain) began in this period, around 1865 (Bean 1981). As a wild plant, it has had a way of bringing out superlatives and passages of purple prose from those who encounter it in flower (e.g. Kingdon Ward 1930). Flower colour varies within these western forms; some pinks are more vivid than others, and white-flowered forms are the norm in most of its Himalayan range (Foster 1996). John Grimshaw (pers. comm. 2021) recalls that in a memorable talk about the Mount Everest expedition of 1953, attended while he was a student almost 40 years later, Sir Edmund Hillary showed a slide of Nepalese forest full of white-flowered Magnolia campbellii, which had evidently made a great impression on the mountaineers. It seems to be merely a historical accident that the type is pink flowered. Foster (1996) noted an individual with rich cream tepals within a white flowered Bhutan population, recording that ‘in the forest its effect was perhaps a touch yellower than that of Magnolia ‘Elizabeth’.

Things became complicated in the 20th century, when Magnolia mollicomata (differing primarily in its hairy pedicels) was described from a series of George Forrest’s specimens collected about 1000 km to the east, in the area where Yunnan meets Xizang (Smith 1920). Subsequently it has been treated as an infraspecific taxon within M. campbellii, either as subsp. mollicomata or var. mollicomata. Seed introductions from the same area quickly followed, most significantly F 24118, 24213 and 24214 of 1924 from the Shweli-Salween Divide, while Forrest’s 1914 gathering from the Dali area seems to have made only a small impact. Trees grown from these collections, along with their unhybridized seedlings, have a distinct set of features. Their tepals are a more subdued mauve-pink than the rose-pink of the western forms; flowers tend to have the ‘cup and saucer’ form prized by gardeners, with an outer whorl of tepals spreading (the saucer) while the incurving inner tepals remain upright (the cup); they flower later in the season than typical M. campbellii, but from an earlier age (10–14 years as opposed to 20–30); and there is a tendency for the crown to spread from an earlier age (Gardiner 2000).

However botanists concerned primarily with wild plants have increasingly rejected “mollicomata” at any level, beginning with Dandy (1928) just a few years after its description. The various characters which distinguish it in gardens vary independently across the wild range of M. campbellii, and when comparing wild specimens from across the range, “mollicomata” does not emerge as a discrete group (Spongberg 1976; Chen & Nooteboom 1993). Early (and ongoing) garden introductions focussed on the westernmost (“typical” campbellii) and easternmost (“mollicomata”) extremes of the range; the clear differences between them reflect this sampling bias. However, this does result in two distinct groups of plants in our gardens. These are long-lived trees, and vegetative propagation is usual, except when breeding new hybrids, so the difference persists. Gardeners need a name for these distinct plants, without being forced to place all garden clones in one or another mutually exclusive category (as is the way with varieties and subspecies), but naturalists should not be saddled with what for them is an unnatural, arbitrary distinction. Hence, M. campbellii Mollicomata Group is here defined (formal publication to follow) on the characters which make these plants distinct in gardens – see below. As with the Cultivar, a Group is intended to be used only for the naming of plants in cultivation (Brickell et al. 2016). Not all eastern forms are included within the Group, notably ‘Lanarth’ and other seedlings raised from F 25655. This collection was made further south than the collections which gave rise to Mollicomata Group, on the Salween-Kiuchiang Divide, Yunnan–Myanmar border, in 1924. These have previously been placed rather uncomfortably in subsp. mollicomata, although differing from those other collections in several ways.

Seed-raised M. campbellii takes up to 30 years before flowering begins. Selected clones are grafted or chip budded, usually onto Mollicomata Group rootstocks. These will generally flower in less than half the time, usually from 10 years. With the blooms being susceptible to frosting, which bleaches out the colour, it is important to site it well. A sheltered yet sunny site with adequate frost drainage is ideal. If a walled site is to be considered, a north wall should be chosen. Heat from a south-, or west-facing wall will cause buds to break too early. It is surprisingly wind tolerant, many trees in SE England suffering only from minor branch breaks in the hurricane-force winds of October 1987.

In Western cultivation, M. campbellii has been most widely tried in the British Isles and New Zealand. In Britain and Ireland, the majority of good specimens are in southern and western areas. Large examples include trees at Caerhays Castle, Cornwall (24.5 m × 333 cm, 2016) and at Castlelough House, Co. Tipperary, Ireland (21 m × 449 cm, 2010 – The Tree Register 2021) but they are many and widespread. Elsewhere in our European area the species can be grown in maritime France and the Low Countries. Climate change has made this dramatic species available to a wider range of gardeners than previously imagined: there are impressive specimens in many eastern gardens in Britain. It remains susceptible to spring frost and it is wise to choose later-flowering selections when planting M. campbellii away from the milder west.

In North America it is grown almost exclusively on the Pacific Coast, from San Francisco north to the Vancouver area (Dirr 2009); East Coast climates simply do not suit it. The first American specimen to flower was probably one in the Strybing Arboretum, San Francisco, in 1940, which still survives, flowering spectacularly each year (e.g. @sfbotanicalgarden Instagram feed, 5 February 2022). Now the San Francisco Botanical Garden, Magnolia campbellii remains an important feature of the garden’s Magnolia Festival in February each year. It has been in the North American nursery trade since 1937 but has never been a mainstream plant (Jacobson 1996). As in Europe, bud and flower damage is a problem in cold winters; during Vancouver’s severe 2008–9 winter, many large specimens at the University of British Columbia Botanical Garden suffered bud loss and even branch death (Justice 2009). It is extremely challenging to grow in the heat and humidity of the American East Coast, although it has flowered for Richard Figlar in South Carolina. It is much more widely grown in New Zealand, on both the main islands, having been in commerce with Duncan & Davies at least since 1915 (Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture 2020). In milder areas flowers are much less prone to frost damage than they are in Britain.

M. campbellii in its various forms has been an important parent of large-flowered hybrids.

Alba Group

Garden plants with white tepals are grouped here, whether or not they have a cultivar name; all seem to have originated from the Indian end of the range, the first introduction being to Caerhays Castle, Cornwall around 1926. Perhaps because they are derived from a very few collections, several other characteristics are claimed as being correlated with white flowers. These are: a tendency to come into leaf much later, often mid-May in Britain; younger flowering of seedlings (12–15 years); larger leaves and flower buds (Gardiner 2000). Named cultivars include:

- ‘Chyverton’ A seedling from the original Caerhays tree, raised before 1975 at Nigel Holman’s garden Chyverton, Cornwall.

- ‘Ethel Hillier’ Raised at Hillier Nurseries before 1973 from wild-origin seed, claimed as especially vigorous and hardy. Faint pink flush on tepal bases outside. (Edwards & Marshall 2019)

- ‘Strybing White’ Distinct flower form: outer tepals hang down while inner ones stay stiffly upright. Selected before 1962 by Eric Walther, Strybing Arboretum, San Francisco, from seed imported in 1940 from Ghose & Co., India.

'Ambrose Congreve'

Tepals claret-red. Selected before 2005 from Ambrose Congreve’s avenue of dark-flowered M. campbellii at Mount Congreve, Co. Waterford, Ireland. ‘Lionel de Rothschild’, from the same source, has rather similar flowers. A number of other clones have been named from this great aveniue, but have yet to achive wide circulation.

'Betty Jessel'

Tepal colour approaching crimson, unusual in being more intense on the upper surface; late flowering. A seedling from the tree later named ‘Darjeeling’, and having much in common with it, obtained by Sir George Jessel (Kent, UK) in 1937, and named for his wife.

'Borde Hill'

See under ‘Lanarth’ below.

'Darjeeling'

Exceptionally dark purple-pink tepals, with the outer whorl reflexed; late flowering. Vegetatively propagated from a tree growing in the Lloyd Botanic Garden, Darjeeling, India; named by Hillier Nurseries by 1967.

'Hendricks Park'

Flowers to 30 cm across; tepals deep, rich pink. Named and distributed (1971 or before) by Gossler Farms, Oregon, from an original tree in Hendricks Park, Eugene, OR.

'Lanarth'

Flowers to 23 cm across, tepals deep magenta ageing deep purple-violet, an extraordinary and striking colour which draws the eye from a great distance in the garden. Early flowering, with the Indian forms rather than Mollicomata Group. Buds larger and flatter than most forms; leaves large as cultivated plants go, typically 25 × 15 cm. One of just three seedlings known to have been raised from F 25655 (Salween-Kiuchiang Divide, 1924 – see main text); this one was planted at Lanarth, Cornwall. Not easily propagated by budding. Seedlings grow vigorously and are often very similar, which has given rise to confusion. ‘Lanarth’ is an important parent of hybrid cultivars. ‘Borde Hill’, another of the three original Forrest seedlings, is very similar in flower and is not discussed separately.

Mollicomata Group

Pedicels densely hairy, rather than glabrous; flower buds more elongated; tepals a more subdued mauve-pink than the vivid rose-pink of the best western forms or the intense purplish-pink of ‘Lanarth’. Flowers tend to have the ‘cup and saucer’ form prized by gardeners, with an outer whorl of tepals spreading (the saucer) while the incurving inner tepals remain upright (the cup). These trees flower later in the season than typical M. campbellii, but from an earlier age (10–14 years), both horticulturally desirable features. Their later flowering makes them more reliable than other forms in mild, maritime climates with start-stop springs. There is also a tendency for the crown to spread from an earlier age (Gardiner 2000). These plants were derived from some of George Forrest’s collections made at the eastern end of the species’ range, in the area where NW Yunnan meets Xizang; F 24118, 24213 and 24214 of 1924, from the Shweli-Salween Divide were most significant; a 1914 gathering from the Dali area seems to have made only a small impact.

The troublesome taxonomic history of Chinese M. campbellii is outlined in the main text. It is important to note that Mollicomata Group as recognised here represents only some of the Chinese forms which have sometimes been shoehorned into M. mollicomata / M. campbellii subsp. mollicomata / M. campbellii var. mollicomata (taxa which most botanists concerned with wild plants have rejected as poorly describing the complex variation in this species). These are the plants to which M. mollicomata was first applied, but seem to form a meaningful group only in gardens.

'Peter Borlase'

Flowers relatively small, 15–20 cm across, an unusual deep rose with a paler central band on the upper surface of the tepals. An open-pollinated seedling from Mollicomata Group, selected 1985 at Lanhydrock, Cornwall by its namesake, from a row of seedlings planted in a shelter belt in 1967; distributed 1989 by David Clulow (Callaway 1992). There seem to have been no suggestions that this unusual plant is an interspecific hybrid. Charles Williams (2022) notes that the flowers give a bicoloured effect, like ‘Betty Jessel’, and that it is the last M. campbellii to flower at Caerhays; he considers it a ‘really excellent plant’.

'Queen Caroline'

Flowers 23 cm across; tepals rich red-purple outside, paler within. Named from a tree at Kew grown from a scion received from Calcutta Botanic Garden in 1904; the queen in question, wife of King George II, was a knowledgeable gardener.

Raffillii Group

Hybrids between western forms with intensely pink tepals and eastern plants of Mollicomata Group, which combine the strongly coloured tepals of the former with the ‘cup and saucer’ form and slightly later flowering of the latter, making it less likely that flowers will be frosted. Charles Raffill of Kew worked on these hybrids in the 1940s, raising about 100 seedlings which were distributed to gardens across southern and western Britain; some are now named. Sir Charles Cave made similar crosses at Sidbury Manor, Devon in the 1920s. The cross may well have also occurred spontaneously in gardens (Bean 1981).

- ‘Charles Raffill’ Flowers 23 cm across, tepals 12, purple-pink outside, white flushed pink inside; slight fragrance. The type for the group, one of several Raffill seedlings planted in the Valley Gardens, Windsor Great Park. Its flowering well after the extreme winter of 1962-3 helped bring this clone to attention. ‘Best selection for cold gardens’ notes Philippe de Spoelberch (pers. comm. 2021). It consistently flowers successfully in April in Ray Wood, Castle Howard, North Yorkshire.

- ‘Kew’s Surprise’ Flowers 23 cm across, richer pink outside than ‘Charles Raffill’; especially good ‘cup and saucer’ form. John Gallagher (Hampshire, UK) also found its buds to be less tender (pers. comm. to Andrews 2006). A Raffill seedling planted at Caerhays Castle, Cornwall, first flowered 1966.

- ‘Sidbury’ Tepals strong pink outside. The only Cave clone distributed, from the original at Sidbury Manor, by Hillier Nurseries from 1970.

'Werrington'

Another of the three seedlings from F 25655, slightly paler and more lavender than ‘Lanarth’ (J. Gallagher pers. comm. to Andrews 2006); raised at Werrington Park, Cornwall, and distributed clonally in a smaller way than ‘Lanarth’.