Juniperus

Credits

Article from Bean's Trees and Shrubs Hardy in the British Isles

Article from New Trees by John Grimshaw & Ross Bayton

Recommended citation

'Juniperus' from the website Trees and Shrubs Online (treesandshrubsonline.

Family

- Cupressaceae

Common Names

- Junipers

Synonyms

- Arceuthos Antoine & Kotschy

- Sabina Mill.

Species in genus

- Juniperus bermudiana

- Juniperus cedrus

- Juniperus chinensis

- Juniperus communis

- Juniperus conferta

- Juniperus deppeana

- Juniperus drupacea

- Juniperus excelsa

- Juniperus flaccida

- Juniperus foetidissima

- Juniperus formosana

- Juniperus horizontalis

- Juniperus komarovii

- Juniperus occidentalis

- Juniperus oxycedrus

- Juniperus phoenicea

- Juniperus pingii

- Juniperus procera

- Juniperus procumbens

- Juniperus recurva

- Juniperus rigida

- Juniperus sabina

- Juniperus saltuaria

- Juniperus scopulorum

- Juniperus semiglobosa

- Juniperus squamata

- Juniperus thurifera

- Juniperus tibetica

- Juniperus virginiana

- Juniperus wallichiana

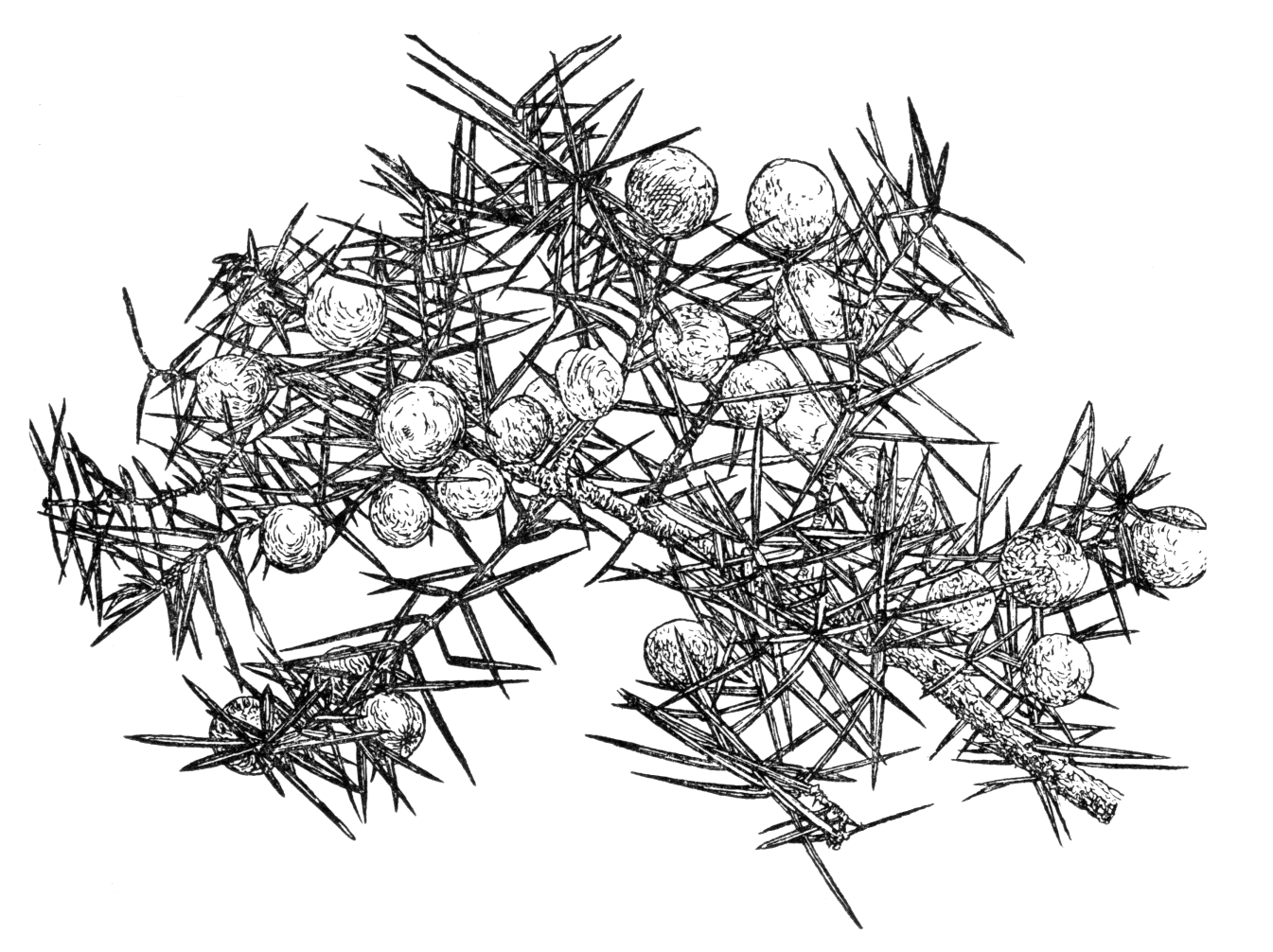

Most genera in the Cupressaceae have narrow distributions and a limited number of species; indeed 18 of the 30 genera are monospecific. In this respect Juniperus is somewhat aberrant, in that it is extremely widespread with many species. The 53 species of juniper (Farjon 2001, 2005c) comprise just under 40 per cent of all the species in the family, and are found across Eurasia and North America, with J. procera extending into southern Africa. The Common Juniper (J. communis L.) is the most widespread of all conifer species. Two further unusual attributes of junipers are the high prevalence of dioecy (monoecy is the norm in the family) and the fleshy cones, which attract animal seed-dispersers. Though commonly referred to as a berry, technically a juniper cone is known as a galbulus. Junipers are evergreen and range in habit from prostrate shrubs to large trees of 30 m or more. The branchlets are terete, four- to six-angled and variously orientated, though typically not flattened. As in many Cupressaceae, there are two leaf forms: juvenile leaves are needle-like, non-decurrent and arranged in whorls of three; adult leaves are scale-like, decurrent, appressed to divergent, and with an abaxial resin gland visible in some species. Mature leaves are decussate or alternate in whorls of three forming six ranks; the lateral and facial pairs largely similar. The male strobili are terminal and solitary on short, lateral branchlets, with three to seven pairs or trios of microsporophylls. The female cones are terminal, solitary, globose to ovoid and mature in one or two years. The seed scales are peltate or valvate, fused together and fleshy or fibrous, or (rarely) woody; they are arranged in one to five pairs or trios, each bearing one to three seeds; the cone is usually berry-like and may be sweet, bitter or resinous; the umbo is small or absent (Farjon 1992, Watson & Eckenwalder 1993, Fu et al. 1999e). The seeds are hard and wingless; parasitic insect larvae can cause the development of cones with bare seeds protruding (gymnocarpy).

Juniperus has traditionally been divided into two large sections: in section Juniperus all leaves are of juvenile form (scale-like leaves being found only on the cone peduncle), while in section Sabina juvenile leaves are restricted to seedlings and the lowermost branches; mature leaves are scale-like, decurrent, decussate or rarely whorled (Farjon 1992). These leaf characters are somewhat plastic, and mutants with unusual leaf morphologies are not uncommon, both in cultivation and in nature. Several members of section Sabina have only a single seed in the cone (monoseed), and in this respect they resemble Microbiota Kom. (Rushforth 1987a). Phylogenetic studies using DNA and morphological data suggest that Juniperus is most closely related to Cupressus and Xanthocyparis (Gadek et al. 2000, Little et al. 2004) (see p. 290), though these studies included only a few representatives of this large genus. As with many other genera of Cupressaceae, the name ‘cedar’ is applied to several species of juniper.

The principal reference works for the genus are Robert P. Adams’ Junipers of the World: The Genus Juniperus (2004) and Aljos Farjon’s A Monograph of Cupressaceae and Sciadopitys (2005c), both of which contain detailed descriptions and numerous illustrations of almost every species. These should be consulted for further botanical details. Very comprehensive illustration of many species and a huge range of cultivars is to be found in D.M. van Gelderen and J.R.P. van Hoey Smith’s Conifers: The Illustrated Encyclopaedia (1996). Many also feature in Richard L. Bitner’s recent Conifers for Gardens (2007). Illustrations appearing in these works are not mentioned in the species accounts that follow.

Juniperus is an extremely important genus of conifers, but has an image problem in consequence of the plethora of dwarfish cultivars, in various colours and shapes, used only too frequently in boring ‘landscaping’. As so often the fault lies not really in the plants, but in a lack of imagination on the part of planters or designers. To compound the problem, many of these cultivars are susceptible to fungal diseases which can cause them to die off in large patches, necessitating their removal. In consequence it seems that junipers are seldom treated with great respect – which is a shame since many, both species and cultivars, have really valuable garden qualities when well sited.

One particularly attractive species, given a short description by Bean (B487), is J. formosana. This has been cultivated for a long time. Dallimore & Jackson (1966) suggest that it may even have been introduced by Fortune in 1844, and it was probably also collected by Wilson (Sargent 1916). A few old trees exist – for example, at Bedgebury, where the oldest specimen was planted in 1935. In 2007 this was 6 m tall, with three trunks, the largest of which has a dbh of 15 cm (D. Luscombe, pers. comm. 2007). Juniperus formosana has been reintroduced in recent years, from both mainland China (for example, SICH 616) and Taiwan (ETOT 89), and is now much more frequent in arboreta than before. As a young tree it makes a beautiful column of pendulous light green foliage, given a special ‘edge’ by the broad white stomatal bands on both leaf surfaces. It seems to be widely tolerant, good specimens having been seen at the JC Raulston Arboretum, Quarryhill and Kew. One species that could certainly be attempted more frequently, especially in sunny, drier gardens, is J. deppeana Steud., the Alligator Juniper, so-named for its beautiful bark, but although popular in North America this is very seldom seen in Europe. It can have excellent blue foliage, and is the most glaucous of all Juniperus species. A superior clone, ‘McFetters’, from Arizona, has done well at the JC Raulston Arboretum (Dirr 1998) and is obviously worth seeking out. It is curious that with the exception of J. scopulorum the western American junipers have received little horticultural attention. Among these is J. osteosperma (Torr.) Little, a familiar, common species of the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau, which would surely make a useful water-wise plant for gardens in the southwestern United States and in the drier parts of Europe. Both of these species can be very slow-growing when young, especially in arid conditions (Nold 2008). From central Asia (Xinjiang, China), usually forming a spreading shrub but occasionally a small tree, is J. pseudosabina Fisch. & C.A. Mey. This has rather glaucous foliage and is considered by Daniel Luscombe of the National Pinetum, Bedgebury, Kent, to be an unusually attractive species (pers. comm. 2008) and well worth growing.

The species described below are mostly collectors’ items, but several have unexpected distributions in the wild that give them an added interest. It would seem that (as can often be the case with tropical members of usually temperate genera) the genes for hardiness have not altogether been lost. Planting sites should however be chosen with regard to origins!

Propagation of Juniperus is by seed, or by cuttings, but these can result in poor root systems that lead to wind rock, especially of columnar forms (Dirr 1998). Several major pests and diseases afflict the genus, especially fungal diseases caused by Phomopsis, Phytophthora and Kabatina which result in dieback of the shoots and often lead to the death of the plant. Bagworm caterpillar infestations are a problem in North America (Huxley et al. 1992, Dirr 1998). There are many others! Planting in a lean, dry, sunny site may help reduce the risk.

Bean’s Trees and Shrubs

Juniperus

Juniper

The junipers are spread widely over the temperate and subtropical regions of the northern hemisphere, the hardy species coming from China and Japan, N. America, Europe, and N. Africa. The only species native of the British Isles is J. communis, which is not uncommon on chalk hills. They are evergreen, and range from trees up to 100 ft high down to low, spreading, or prostrate shrubs. The bark is usually thin, and often peels off in long strips. Leaves of two types: (1) awl-shaped, and from 1⁄2 to 7⁄8 in. long, borne in whorls of threes or in pairs; (2) small, scale-like, and rarely more than 1⁄16 in. long, arranged oppositely in pairs and closely appressed to the branchlet. The first kind is found on the juvenile plants of all species; and several species, notably those of the communis group, retain it permanently. But other species, namely, those of the Sabina section, including J. virginiana and chinensis, as they get older develop more and more of the minute scale-like type of leaf which is essentially characteristic of the adult plant. A number of species, long after they have reached the fruit-bearing stage, continue to produce the juvenile as well as the adult type. This peculiarity is, however, apparently more characteristic of cultivated than of wild specimens. The flowers are unisexual, and most frequently the two sexes occur on separate trees, sometimes on one. The male flowers are small, erect, columnar or egg-shaped bodies, composed of ovate or shield-like scales, overlapping each other and each carrying anthers at the base. The fruit is composed of usually three to six coalescent, fleshy scales, forming a ‘berry’ that carries one to six seeds. It is this fruit that distinguishes the scale-leaved junipers from Cupressus, which they much resemble in foliage. Without fruit, the junipers can usually be recognised by a peculiar, aromatic, somewhat pungent odour, especially strongly developed in the savin.

Junipers like a well-drained soil, and most of them are lime-tolerant. This gives the genus a special value in chalky districts, where the impossibility of growing satisfactorily most of the heath family somewhat limits the number of evergreens available. Many of the species take two years to ripen their fruit, and the seeds will often lie dormant a year. Their germination may sometimes be hastened by plunging them in boiling water from three to six seconds, but this should only be regarded as an experiment, and tried with a portion of the seeds. All junipers can be increased by cuttings, a method especially suitable for the shrubby sorts.

From the Supplement (Vol.V)

A very useful assessment of the many junipers of low, spreading habit, based on trials held at Boskoop, will be found in Dendroflora No. 21 (1984), pp. 3–38, with an English summary. On p. 34 there is a list of cultivars which are not recommended (left-hand column) and of those by which they have been superseded (right-hand column).